31 Years of Horror

One spooky (or unseemly) movie for each of the last 31 years. Because how long is anyone 31?

‘Tis the season.

The problem is, they were these 31 years. A time that any serious fan of horror cinema will tell you was a dark and fallow time for the genre at large. With the golden age of the exploitation independents having petered out by the end of the ‘80s, even casual horror fans had grown leery of all the franchise offal (five Nightmare on Elm Streets, five Halloweens, and eight Friday the 13ths by the end of the decade — not that there aren’t a couple of decent Nightmares and Fridays buried in there), and in the ‘90s…well, in the ‘90s, people just didn’t want much of any horror. (Broadly speaking, of course.) And if they did, it tended to be diluted through sci-fi action-thriller premises. The early-/mid-‘90s were particularly desolate as far as crossover appeal for the genre was concerned, and only with the meta-winking Scream in 1996 did the slashers make a tepid resurgence.

The ‘00s weren’t much better — in that they were at least as bad, but were preferable for the genre if only because at least there was a revival of interest. People finally wanted to feel some sting again — and these days, they want it even more. (Either that, or wallow in revulsion.) Nobody needs a reiteration of all the socio-political underpinnings of the ‘torture-porn’ wave that came in the wake of two brand-spanking-new American Wars™, blah blah blah…long story short, I had to dig deep to fill all 31 of these slots. And I emerge unlikely to impress any (*checks notes*) ‘hot e-girl camsluts’ with the fact that I now have Demon Wind (1990), Dolly Dearest (1992), The Paperboy (1994), Species (1995), Strangeland (1998), and One Missed Call (2003) under my belt.

I was born in 1989, but it wasn’t until the very last week of the decade that I actually drew breath, and so I played by my own rules and started at 1990. This made the task even more frustrating, because 1989 has at least three first-rate horrors just off the top of my head - Brian Yuzna’s Society; Bob Balaban’s Parents; Shinya Tsukamoto’s Tetsuo: The Iron Man, if we cast the net a little wider - that are better than most of the movies on this list.

And yet.

We kick off at the bottom of the barrel. The Suckling is about a woman who’s manipulated into a back-alley abortion - this clinic doubles as a brothel - and the fetus, flushed into a sewer of toxic waste, quivers and mutates into that giant carnivorous monster you see above.

You could say it’s a film in bad taste. You could also say that the director, Francis Teri, never made another movie, and that the one he did make is piled high with actors who are hella stilted — even by the standards of fetus-monster movies.

What Teri has, though, is that monster, which really is a wonder of fleshy low-budget practical effects. It’s got the bald, oval head of your standard-issue movie martian, but the whole creature is held together by tight-bare musculature, with gelid eyes and a jutting mouth of long angler-fish teeth. In the same way that a cult classic like The Deadly Spawn (1983) would’ve been simply embarrassing without frequent payoffs of its glorious monsters, The Suckling would’ve been completely unwatchable without quite so vivid a suckler.

Now, there’s also the question of how much social satire there’s supposed to be here, if any, and in what direction. I don’t (yet) own Vinegar Syndrome’s blu-ray, which features an interview with Teri where he presumably elaborates. It certainly seems as though the movie’s drawing direct lines between abortion/depravity/toxicity, and the movie’s ‘drama,’ such as it is, mostly revolves around the clinic-brothel’s occupants turning on themselves — the baby’s would-be father is particularly overrun by paranoia. (‘I’m gonna kill this thing…before it gets…any bigger.’) And yet the movie certainly doesn’t call into question the vacuous mechanics of its would-be family, à la Larry Cohen’s It’s Alive (1974), the standard in giant-headed baby-monster movies.

Until I get further context, though, I’d still tend to agree with another online reviewer who proffered that no one so vociferously pro-life ‘would consciously put this much effort into something so off-putting.’ Or at least, probably not through a cheap-o monster-splatter movie. The Suckling basically dismantles such questions of politics early on, in a scene where a topless dominatrix uses her whip to lasso a wobbly dildo out of the hands of a guy who’s wearing one of those goofy helicopter hats. I mean, what can you say?

I almost went with Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro’s Delicatessen here. It’s not an outright horror movie, but it has some sophisticated comic-nightmare compositions and a crisp golden-orange palette (courtesy of the great Darius Khondji) that feels pretty autumnal, even if the titular delicatessen is surrounded by desiccated black-skied industrial charnel. (Alas, Jeunet: never quite as good after Caro split.)

Somewhat reluctantly, though, I’m going with Wes Craven. ‘Reluctantly’ because Wes Craven was…let’s face it…a bit of a hack. Or at the very least, he allowed his craftsmanship and serious study of the macabre to be readily-plundered by, shall we say, craven interests.

Now, it’s true that no other filmmaker can be said to have re-invented (or at least commercially re-calibrated) the horror genre three separate times: with the exploitation ‘rape-and-revenge’ grisliness of The Last House on the Left (1972); with A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), one of cinema’s most deeply tragic cases of a sublime concept compromised by shallowness; and with Scream (1996), a fun little mystery-slasher with an obnoxious winking streak. Truly, the man was a cinematic Miles Davis. Pfffhaha.

And yet, among the big American horror auteurs of the Boomer generation (what, as opposed to all the towering horror auteurs of subsequent generations?), the personal flavors are scarce with Craven. He never had John Carpenter’s hypnagogic atmospherics and soothing classicism; he never had Tobe Hooper’s aptitude for the almost unbearably intense ‘endurance-test’ crescendo (though parts of The Hills Have Eyes (1977) and Scream’s last 20 minutes are laudably intense); he never had George A. Romero’s sense for the dizzying cut — nor, yes, his social consciousness.

Except in the case of The People Under the Stairs! Which is about a pre-teen boy nicknamed ‘Fool’ (Brandon Adams) whose family is being evicted from their impoverished ghetto apartment. He’s convinced by a young Ving Rhames to break in to the labyrinthine house of the slumlords, a married couple, in order to find some rumored gold. What’s discovered between the house’s walls - literally - is…well, put it this way: it’s like Home Alone, but with incestuous cannibalism replacing all the stupid pratfalls and cutesy sentimentality. The tone shifts so often, so broadly, so quickly, that it’s hard to get any one footing — but that’s what makes it such a hoot! Oh, how I would’ve loved this movie as a child!

The slumlords, who call each other ‘Mommy’ and ‘Daddy’ and are played by Everett McGill and Wendy Robie (Big Ed and Nadine in Twin Peaks), are clearly meant to evoke Ronald and Nancy Reagan: they look like them, sorta, and they’re literally keeping the oppressed classes in the basement to feed on each other. As a measure of how ill-equipped the early ‘90s were for serious horror, you can check out a Siskel & Ebert episode where Siskel parrots Dave Kehr’s read of the film - as a horror-movie parable for Reaganomics (which is obviously what it is) - and it’s funny both because (a) Siskel explains Kehr’s read as if it’s a really deep one (‘Stay with me on this wild theory!’), and (b) Ebert just laughs it off as a tortured analysis. I guess it is a sign of progress that today’s middlebrows, watching The People Under the Stairs, would presumably be smart enough to spot the writing on the walls.

The movie’s climax/denouement flails on for far too long, and the closing music is corny. Plus there’s some typical bad-horror-movie choreography where characters take forever to stand up after they fall down or trip or whatever. But the wild ambition here is a joy: it’s a children’s-adventure fantasy, but with all sorts of high-angle shots of the house’s passageways contrasting against tilted, unsettling close-ups to make the house feel huge. And the movie’s also laugh-out-loud funny at a few points: the riled-up exchanges between McGill and Robie; a set of shutter doors abruptly swinging open for someone to physically snatch the action away; the way Fool at one point just up and punches a dog in the face.

There’s also a surprisingly good performance from A.J. Langer as the slumlords’ young ‘daughter’ (prisoner), Alice: she has a really convincing anguished face, and toward the end gives the realistic impression that she’s just barely holding on to her newfound bravery. And Ving Rhames delivers some broad one-liners that crack me up, in a dumb way. (‘I done busted this house’s cherry!’)

Alternative title: Boyz n the Hood, Kids in the Hall.

Most people would go with Bernard Rose’s under-refined Candyman for ‘92, or Peter Jackson’s Dead Alive. And the ambitious BBC Ghostwatch deserves a shout-out.

But The Cat, the last film directed by Lam Nai-choi - best known for his martial arts splatter film Riki-Oh: The Story of Ricky (1991) - is about a cat from outer space who teams up with a young girl in order to fight a fungus-y alien that possesses people. So, I think this choice was clear.

This movie features a bit of everything that flourished so vividly in the Hong Kong film industry from the ‘80s through the mid-‘90s. There’s exhilarating gore gags and body horror; psychedelic-grindhouse imagery; a bit of kaiju; lots of gunplay; an effectively ominous (and sometimes quite pretty) synth-and-bells score…and, halfway through, the clincher: a manic fight scene between a cat and a dog - surely the best ever put on film - which had the audience in rapture when I saw the movie in a theater. (I was already in some sort of rapture myself, having been ‘coming up’ during some lovely nether-heaven images of rear-projected stars.)

Best Hong Kong ‘horror’ movie since A Chinese Ghost Story (1987)?

This is a rare thing: a horror anthology that works. I’m always amazed that there aren’t more and better ones - it seems so fertile a template! - and yet I suppose that if even Mario Bava (Black Sabbath, 1963) and George A. Romero (Creepshow, 1982) emerged with only mixed success, there’s probably something more complex about the endeavor that I’m not realizing.

Featuring two stories by John Carpenter and a closing one by Tobe Hooper, the Body Bags program is MC’d by Carpenter himself, playing a comic mortician who’s a hell of a lot funnier than the Cryptkeeper. (‘Natural causes…natural causes…I hate natural causes!’) The middle segment, “Hair”, gets goofy: the great Stacy Keach plays a vain man who can’t accept the fact that he’s balding, and invests in a toupée that has some less-than-ideal long-term effects. It’s a right-thinking parable about the pathetic-ness of fearing your own age. But it’s not scary at all.

It’s the first and third segments that get genuinely creepy — not consistently, and never mind-bendingly so, but they both show a few inspired moments of dread. In the first, Carpenter’s “The Gas Station”, a young woman takes the night shift at a remote fill station while a serial killer remains on the loose in the area. There’s not much to it, beyond her interacting with a few customers and eventually encountering the killer, but the buildup and reveal of the killer’s identity is done with a chilling coldness, and features what must be the most disturbing cutting of a phone line in cinema history. Crucially, the late-night dread is reinforced by one of Carpenter’s bleariest synth scores - almost tragic - which continues unhurried through some bits that anyone else would’ve pumped-up prematurely. There are some nifty visual effects, too, like one part where our protagonist accidentally steps on a tire hose and the camera whiplashes with the noise, so that it looks and feels like we’ve been shot in the head. And the whole segment ends with a gloriously climactic burst of red paint-blood.

Tobe Hooper’s segment, “Eye”, stars Mark Hamill as a baseball player who gets in a car accident and damages one of his eyes. Consenting to some experimental surgery, he gets a new eye from a recently-departed fella who just so happens to have been a serial killer who liked to fuck his victims’ corpses. A goofy concept, to be sure. There isn’t much more to it, except that Hamill’s climactic ‘turn’ where he attacks his own wife is genuinely (albeit briefly) harrowing, and re-ignites that ‘endurance-test’ quality that makes Hooper’s cinema so memorable — in both his Texas Chain Saw Massacres (1974/1986), in Eaten Alive (1977), and in the climaxes of both The Funhouse (1981) and Poltergeist (1982), a sequence which does seem to have nearly as much Hooper as Spielberg in it.

Side note: I was actually really surprised to learn that the writers of that late (season 10) Simpsons “Treehouse of Horror” episode where Homer gets the murderous toupée actually wasn’t based on a combination of “Hair” and “The Eye”, but on an Amazing Stories episode from 1986. But I’m still betting that the writers had Body Bags somewhere in the back of their minds.

I had a few decent options for 1994. John Carpenter’s In the Mouth of Madness is an obvious one, a party pileup of Lovecraftian nightmares that proved the old master still had some uncanny tricks up his sleeve. (That late-night highway scene!) It’s the last movie Carpenter got ambitious the whole way through for.

And there’s also the oft-maligned Brainscan, directed by John Flynn of Rolling Thunder (1977) semi-fame, wherein Terminator 2’s disgruntled Edward Furlong, home alone in one of the most tricked-out bedrooms in all of moviedom, discovers a computer game of ‘interactive terror’ and winds up manipulated into becoming the neighborhood slasher. The movie’s pretty lame whenever it checks in on ‘Trickster,’ the punk-rock Freddy Krueger/Beetlejuice mashup and Primus fan (?) who serves as the game’s avatar. But as a relaxed hangout movie about being a mopey ‘90s boy, crushing on the girl next door from your room of technological splendor (giant bubbling tube lamp! voice-activated phone calls! ), it’s a warm bath. And Frank Langella commits.

Even Tim Burton’s Ed Wood has always felt very spooky-seasonal to me, especially with that wonderfully adult transposition of a creepy Halloween night — now in the house of the real Bela Lugosi.

But I’ll go with Cemetery Man, a.k.a. Dellamorte Dellamore, a capstone to the great era of Italian horror cinema to which director Michele Soavi was a late-stage adherent. (Check out his 1987 Stage Fright for a fun late giallo set in a stage theater.) With Dario Argento in the throes of his rapid and irrevocable decline, and Lucio Fulci nearing death (and even further from his golden period than Argento), Soavi took one last heroic swing for the fences with Cemetery Man. Gorgeous lovelorn Rupert Everett plays a cemetery keeper who’s shunned by the rest of his small Italian town, but has to keep killing off the rising undead in order to protect that same town. His only company is the squat scene-stealing assistant Gnaghi (François Hadji-Lazaro), who is only capable of saying one word: ‘Gnaaa!’ (‘Distinctive visible marks: all.’)

Falling in love with a nameless widow (Anna Falchi), who herself ends up continually rising from the dead, we follow Everett further and further into crazyville as he begins to become so morbid and victimized that he starts going beyond zombie-killing and into straight-up homicide, figuring that he might as well cut to the chase and incapacitate people before they rise.

It’s a zombie sex farce, sort of, but with an an endearingly brooding and goth-y view of death as something both comforting and practical (I’d give my life to be dead’), and it gets more and more absurd as it goes on — arguably, to the point of being overstuffed. The pileup of jokey Army of Darkness-style throwaway gags does make the movie feel longer than it is. But how can you not look fondly on a film that features a shot from inside an airborne chomping mouth?

Plus, this cemetery is a stunner — a real cemetery, too: balmy with fog, spidery decay draping and poking everywhere within this worthiest of resting places.

Despite the general dearth of horror movies in the early-/mid-‘90s, there was a curious deluge of vampire films: John Landis’s wintry mobster-erotica-bloodsucker mashup Innocent Blood (1992); Guillermo del Toro’s feature debut Cronos (1993); Michael Almereyda’s NYC-hip Nadja (1994); Abel Ferrara’s black-and-white heroin metaphor The Addiction (1995); Wes Craven’s ridiculous Eddie Murphy vanity project Vampire in Brooklyn (1995). (John Carpenter jumped on the bandwagon late, with his 1998 Vampires — one great James Woods performance and an excellent first 25 minutes, diluted by Tarantino coppery and a bad rock soundtrack.) Presumably, this boom was an attempt to court the nascent horror market using the backdoor entrance of the then-popular ‘erotic thriller.’ But Larry Fessenden’s Habit is the only one of the ‘90s vampire crop with enough, err, bite.

Habit begins at a Halloween party, where Sam (played by the auteur himself) has just broken up with his girlfriend Liza (Heather Woodbury). There he meets a soft-spoken short-haired beauty named Anna (Meredith Snaider), who correctly marks Sam as ‘very compulsive’ from the moment she sets eyes on him. This sets in motion the rebound of all rebounds, with Anna reappearing only by night for kinky public sex that, yes, tends to involve a little bloodletting. Nothing gushing: just some bites here and there that break the skin a little harder than is typical — all of which Sam (understandably) goes along with as a kink.

We follow Fessenden all around Giuliani-era New York City, plus a sojourn upstate for a friends’ Thanksgiving (it’s an admirably seasonal film), as he gradually figures out - only through his dreams, it should be noted - what Anna’s whole deal is. Through many acutely-observed character scenes, we come to realize a great deal about Sam and his milieu: shiftless, vaguely bohemian, vaguely schmucky young people who look and sound a lot like the shiftless, vaguely bohemian, vaguely schmucky millennials of today.

Where Abel Ferrara’s The Addiction is basically a heroin metaphor (or an AIDS metaphor, if you want it), Habit can be metaphorical for any addiction - and the thrill and shame that results - without turning into too much of a bummer and without losing its creepiness. Liza points out to Sam early on that she doesn’t want him ‘going crazy just ‘cause there’s no one to call you on it,’ and though she’s mostly referring to Sam’s alcoholism - which teeters ever-further back toward a past of violent self-destructiveness that we only gradually glean - that’s a danger that a great many of us skirt regularly. There really is nothing else between Sam and Anna other than the sex (usually scored tragically), whereas ex-girlfriend Liza seems heartbreakingly lovely. (Fessenden has a great eye for lingering with disappointed women.) And there’s some great detail about friends cornered into becoming enablers: when Sam’s friend Nick, who I liked a lot (played by Aaron Beall), lectures him about cutting back on the booze, Sam starts breaking down and Nick immediately tries to cheer him up by suggesting they have a drink.

Habit is Fessenden’s second film, but it sure has the feeling of a debut: there’s that sense of a movie made by someone who isn’t sure if they’re gonna get to make another one. (It took six years for Fessenden’s next feature to come out.) I found it significantly more visually fascinating, emotionally stirring, and fucking artful than, say, Claire Denis’s cold-fish cannibalism movie Trouble Every Day (2001), to say nothing of some piece of crap like Let the Right One In (either incarnation). With its weedy protagonist and ‘gritty’ look - grittier than most ‘90s horror movies, anyway - Habit recalls George A. Romero’s brilliant, still-underseen vampire flick Martin (1977), but Habit is a significantly sadder film. ‘Everyone I know’s goin’ their separate ways,’ Sam laments offhandedly at one point, and there is indeed a sense that the aforementioned ‘shiftlessness’ might turn into a bad habit all its own.

Habit is certainly not as capital-R Romantic of a film as Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark (1987), another movie about an unsuspecting young man who gets drawn toward vampirism, which in a few scenes touches the cosmic potential of insatiable immortality in a way that no other vampire film has. (‘That light that’s leaving that star right now will take a billion years to get down here. You wanna know why you’ve never met a girl like me before? Because I’ll still be here when the light from that star gets down here to earth.’) But on the other hand, I care more about Larry Fessenden’s Sam than I do about Adrian Pasdar’s Caleb.

The film’s only significant drawback, other than the eyesore of a poster, is the prevalence of a lot of wispy-droopy indie-folk music, presumably included for levity’s sake but which tends to trivialize some mesmerizing cross-cutting that would’ve been beautiful enough on its own. (There’s a very brief sequence on a ferris wheel that has a flavor of vertiginousness rarely seen since the ‘70s.)

I caught up with some of Fessenden’s other films over the last month, making the mistake of starting with 2001’s domestic-drama-among-the-rednecks movie Wendigo. (I thought it was unremarkable, save for some really cheesy effects - sometimes apparently intentionally; he seems to like stuffed-animal deaths - and an alarmingly bad performance from Patricia Clarkson. The opening credits look like a high school slide show presentation.) But then I backtracked and found Habit, and later the ambitiously dread-inducing The Last Winter (2006), and…honestly, it’s one of the best movies on this page! (The closest things to runners-up for ‘95 were Spike Lee cinematographer Ernest Dickerson’s fun undead-siege romp Demon Knight, featuring a delightfully scenery-chewing performance from Billy Zane, and Re-Animator director Stuart Gordon’s under-seen Castle Freak. And Rusty Cundieff’s Tales from the Hood is a very admirable attempt at a ‘ghetto-horror’ anthology movie, even if most of it doesn’t quite work.)

There’s a scene toward the end of Habit where Sam finds a murdered body, and this is the only movie I’ve ever seen where someone finds a bloody corpse, touches it, wipes the blood off on their own shirt…where it actually makes sense in the moment, and I’m not shouting at the screen. Because in that moment, cumulatively, it feels traumatic enough that when Fessenden actually pauses for a couple of beats before wiping his hands, it’s realistically absent-minded. Just to get it off.

Not your typical ‘horror film,’ for sure, but I was desperate for ’96. (I’ve never cared for Peter Jackson’s The Frighteners, and it would’ve been pretty weak if I’d had to fall back on Scream.) Herman Yau’s dictionary of depravity, made in the waning days of the Hong Kong film industry, isn’t ‘spooky’ at all — ‘appalling’ is more like it. In fact it’s hard to think of a movie that so consistently depicts so much depravity so casually: rape, murder, dismemberment, cannibalism — fun for the whole family!

Ebola Syndrome is carried by an off-the-chain performance from Anthony Wong, playing one of the most casual sicko reprobates in movie history. The film opens with Wong fucking his boss’s wife, and within a few short minutes he’s brutally murdered both the wife and the boss, fleeing to South Africa where he gets a job as a chef in a Chinese restaurant. (At one point, he masturbates into a piece of raw meat and then puts it back in the pot for cooking.) While on safari in Africa, Wong rapes and murders a near-catatonic tribeswoman who’s infected with the Ebola virus, and the rest of the movie follows Wong as he spreads the disease willy-nilly across South Africa - by feeding the patrons burgers cut from his new rape-and-murder victims, naturally - and eventually back in Hong Kong.

I seriously can’t emphasize the word ‘appalling’ strongly enough: Ebola Syndrome is a grotesque experience, horrifically sexist and racist at that. But it’s also…quite funny, in the sense of watching a train-wreck of a human being continue to go further and further without any shame or guilt — just loud annoyance at the ‘bullying’ he sees from literally every single person who isn’t him.

It’s a movie to watch with your jaw agape, the chuckles stalling in the throat, but there’s a place for such a purely sickening film among a horror-movie lineup — especially one that can still make you laugh. And though Ebola Syndrome calms down a bit (very relatively speaking) in its third quarter, with some confusing stylistic additions (slow-motion shots of people touching infected material; shots from inside people’s mouths) and some bad English-language actors, it revs back into full force for an unforgettably absurd finale where Wong runs down the streets of Hong Kong, pursued by police in hazmat suits, spitting in bystanders’ faces and shouting, ‘Ebola! Ebola!’ It’s…crazy.

I was coming up so short in ’97 that I almost went with Pooh’s Grand Adventure: The Search for Christopher Robin. (Admittedly not as creepy to me at 31 as at seven.) But The Relic, directed and photographed by Peter Hyams (Capricorn One; 2010), is just a fun little monster movie, set in a big museum and shot in a lot of rain and darkness. It’s about a hideous giant lizard-like monster that makes its way from a South American tribe to Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, where it terrorizes the guests at a big black-tie fundraising event.

Nothing groundbreaking here, but the movie has a great setting, some enjoyable pseudo-science, a terrific cast of character actors (Tom Sizemore, Penelope Ann Miller, James Whitmore, and the wonderful Linda Hunt), and some excellent Stan Winston effects with the creature whenever it’s not moving around with dated ‘90s CGI. That creature seems part-reptilian, part-arachnid, with interlocking tusks for decapitating its victims and feasting on their brains. What more can a boy ask for?

1998 gets really into the dregs. The tragic-tinged Korean Whispering Corridors isn’t quite spooky enough to qualify. John Carpenter’s Vampires is a fun James Woods performance and a really fun first 25 minutes. Ringu, yeah yeah, we’ll get there…but then what? Gus van Sant’s Psycho remake? Dumbass teen slasher shit like Urban Legend or I Still Know What You Did Last Summer, none of which even had the courtesy to offer the nudity that the ‘80s slashers provided so readily? Or should I have gone with a Japanese ‘pink’ film that would weird everyone out?

So, The Faculty. The high school body-snatcher movie with a fun hang-out vibe. As with screenwriter Kevin Williamson’s Scream, the movie works both as a chase-prone horror movie (especially when our band of teens tries to escape the high school during a crowded football game) and as a Thing-like mystery (which of these teens is already infected?) — as all proper body-snatcher movies should.

A lot of stuff in The Faculty ages poorly, relics of an enervated era: Josh Hartnett; Harry Knowles; the entire soundtrack. (Ever wanted to hear Creed cover Alice Cooper? What’s that? ‘No,’ you say? ‘Kill it with fire,’ you say?) And yet it’s still easily my favorite Robert Rodriguez movie. How often does one get to see Piper Laurie, Jon Stewart, Bebe Neuwirth, and Usher in the same movie?

It really was ‘lightning in a bottle,’ y’know. And the evidence of that is…every other movie directed by Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez — none co-directed, and all of which are so generic and/or dreadful that you’d never suspect these guys could’ve ever bottled lightning in the first place.

(For the record, Myrick is the ‘tidier’ one; the one who knows how to put a movie together in the sense of lighting, shooting, and cutting just competently enough to be release-able, at the bottom of a Canadian Netflix horror section. He's also the one with ‘ideas,’ which take forever to wind down into an inevitable revelation about stuff we don’t care about. And he was also able to net the most ‘name’ cast of either of the two directors: R. Lee Ermey, Amanda Seyfried, and the kid from Road to Perdition in the generic teen summerhouse swampland movie Solstice. Sánchez, meanwhile, is the shaky-cam guy, more horror-centric and with little pretense to ‘ideas’; his movies are certainly more effective as horror than Myrick’s, but his vibe is way more irritating. No sense for dialogue at all with that guy.)

Anyway, The Blair Witch Project is by now apparently regarded as one of those popular, critically-respected American movies of 1999 like The Sixth Sense or The Matrix or Fight Club: movies which blew minds at the time, but which suffer sharply with age/repeated viewings/dilution of the gimmick. In my experience, even a lot of people who loved Blair Witch at the time come back to it and say, ‘Eh, not nearly as great as we thought.’

For me? Just the opposite experience. I first saw the movie shortly after it came out on video, when I was 10, while on summer vacation at a cottage surrounded by forest. (My mom loved the movie; my dad, already witnessing the degradation of the English language in real time as a high school teacher in the ‘90s, counted the swears.) I could, and still do, get scared in the woods at night, and I watched the movie under these pretty ideal circumstances and thought it was...okay. Just okay. The last few minutes definitely unnerved me, but I wasn’t scared much by the unraveling and mounting hopelessness that comprises most of the film. The characters seemed foolish for the conveniences of the momentum and/or gimmick, and it ‘wouldn't've been how I’d’ve handled the situation.’ So even though the Blair Witch backlash felt silly and overly-defensive even at the time, I was in the ‘Perfectly respectable and original, but ultimately not all that scary’ camp.

I saw the movie again a few years ago and was blown away. It left me very rattled. Formally, it’s a lot more clever and subtle than we now give it credit for; it resists so many of the dumb decisions that cheapen even the good ‘found footage’ movies. No phony dips and hums in the audio to serve as de facto sound design ([REC]); no assumptions that we need to know more banal domestic details of these characters’ lives (Paranormal Activity); no attempt to look polished or even theatrically-releasable (The Visit). Most of the screen is dead grass in cheap daylight. The situation progresses quickly, but at the same time it never feels like we’re being rushed along by filmmakers who worry that we’re getting bored.

The complaints that these three characters yell and gripe at each other too much simply don’t hold up for me. Maybe it’s because I now understand more clearly the varying levels of desperation that these thrifty twentysomethings pass through and try to rationalize, but honestly this just seems like, ‘Yup, that's pretty much how it’d go down in ’99.’ Not only are these actors actually pretty good - something that couldn’t be said about the previous year’s The Last Broadcast, which predates Blair Witch as found-footage horror but isn’t scary; I don’t sense a lot of straining for naturalism here like I do with almost every other ‘found-footage’ horror movie - but I was struck by how convincingly each character fell into the roles of being the one who comforts, the one who jokes, the one who’s angry, the one who despairs. And by the convincing intervals in which those roles arrived. These modes come and go, and the movie in its wholeness reveals them all as different shades of denial. When they find out the map has been thrown away, the immediate spew of terror and rage (against the guilty’s laughter) reveals just how thin this ice really is. And while I grant that the act of throwing away the map is a totally absurd development...well, so is walking straight ahead all day and ending up right back where you were in the morning. So is a witch. The witch made him do it. As for the oft-ridiculed ‘inability to stop filming,’ well, I grant that it wouldn’t’ve been as questionable if the movie didn’t keep calling attention to it. But even there, I can’t count too many sequences that feel unbelievable — it’s all egregious because they’re in love with the fact that they can do this. Even the interview subjects - I love the infant trying to cover its mother’s mouth; how’d they get the kid to do that? - seem real, except for those fishermen.

The incremental degree to which the situation is left juuuust on the right edge of a waking nightmare - not shrieks and moans surrounding the tent at night, but crackling rocks and whispering children; not lungs or intestines left in the bag, but hair and a little piece of tongue - is carefully sustained As everything continues to unravel, the memories of both the ominous hearsay in the interviews (a woman hairy from head to toe whose ‘feet never touched the ground’ — that’s great creepy American folk imagery) and the reality that feeds the lore (the murdered children) are amplified and left to rattle around in your head to fight and squirm and deny...until the end, when we arrive at the house. And that house is no gothic chamber, no druid’s hut — it’s just...a house, just a shitty run-down house that looks like an abandoned crank lab. This is witchcraft played as the hard physical reality of a bad trip; a vicious past encroaching and then arriving at a corrupted present, which seems all the more terrifying when you’re suddenly made to come to terms with all the time you wasted leading up to this moment. In other words, the banality of the early stuff is absolutely crucial to the effect of the ending. In that one scene when they’re literally shaken out of their tent and they plunge into the deep dark woods…that’s a viscerally terrifying moment: these people could be anyone, in any random woods, running from some horrifying force that’s totally beyond their understanding and control.

‘The scenes of our life are like pictures done in rough mosaic. Looked at close, they produce no effect. There is nothing beautiful to be found in them, unless you stand some distance off. So, to gain anything we have longed for is only to discover how vain and empty it is; and even though we are always living in expectation of better things, at the same time we often repent and long to have the past back again. We look upon the present as something to be put up with while it lasts, and serving only as the way towards our goal. Hence most people, if they glance back when they come to the end of life, will find that all along they have been living ad interim: they will be surprised to find that the very thing they disregarded and let slip by unenjoyed, was just the life in the expectation of which they passed all their time. Of how many a man may it not be said that hope made a fool of him until he danced into the arms of death! [...] In the first place, a man never is happy, but spends his whole life in striving after something which he thinks will make him so; he seldom attains his goal, and when he does, it is only to be disappointed; he is mostly shipwrecked in the end, and comes into harbor with masts and rigging gone. And then, it is all one whether he has been happy or miserable; for his life was never anything more than a present moment always vanishing; and now it is over.’ — Arthur Schopenhauer, Studies in Pessimism

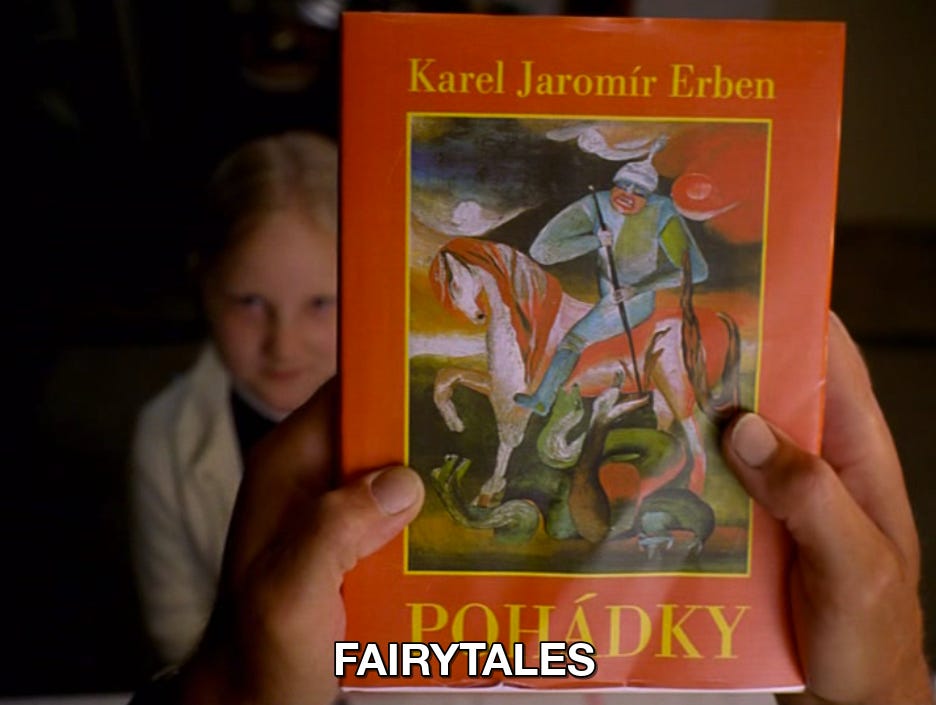

From Jan Švankmajer, the surrealist Czech animator best known for that bizarre stop-motion Alice in Wonderland movie (1988’s Alice) that traumatized so many an unsuspecting child. He’s like an even more unseemly Terry Gilliam.

Little Otik, based on an old folk tale, concerns a couple who can’t have a baby, and so the husband - as a joke - brings home a vaguely-human-shaped piece of log (which he gets by, um, yanking on a stump)…which the mother then starts enthusiastically raising as her own child.

As you’d guess, the log eventually - ‘at long last,’ I’d say; Švankmajer’s movies are usually too long - starts coming alive and doing all sorts of nasty things: sucking his mom’s hair into his anus-y mouth-hole at first, then growing bigger and bigger until it starts eating neighbors and has to be contained in a big chest, its wooden tendrils crawling out to…eat cabbages? I’m foggy on some of the details.

Švankmajer’s films looks staled and ugly in the way that so many ‘70s European films do (many of them masterpieces, of course), and I do wish there were more, um, animation here. More Otik, please! But Švankmajer’s film is unseemly even before the log starts moving. He cuts a lot - a lot - but despite the addled rhythm his films always stay very tactile — ickily. Even the briefest of incidental shots are laced with queasiness, especially when it comes to food, of which Švankmajer is cinema’s most grotesque chronicler. Seriously, the food looks gross even before the characters start smearing it through their gobs. (Whipped cream on pickles, anyone?)

Reinforced by the Czech language, which (I’m sorry, but) has gotta be in the running for Ugliest-Sounding World Language, you get an almost oppressive experience that’s at least a half-hour too long - hell, 45 minutes too long - but is, in its way, somehow even ickier than Ebola Syndrome. And Little Otik doesn’t even have any rape or cannibalism!

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse is, in my judgment, the best and least-dated film from that wave of Japanese horror movies (‘J-horror’) where the supernatural emerged from and within Technology — basically, ghosts coming out of TVs and computers and whatnot. It follows two characters (separately, but eventually converging) who are both led to discover a series of unsettling computer videos: ghostly figures, their faces blurry and vacant, moving more and more uncannily with each unprompted appearance.

These ghosts - and they are ghosts - don’t ever physically hurt anyone (though they are also material): they simply confront people with so horrible a face of death - and the knowledge that with death, nothing changes - that the characters end up either committing suicide in despair, or simply dissolving into the air itself (or into cloudy blurs on the wall that are reminiscent of reports from Hiroshima that some ‘shadows’ were left imprinted). At one point, a character does the thing one might do in their lucid nightmares, confronting the threat head-on with the knowledge that they aren’t ‘real.’ (‘I refuse to acknowledge death!’) But the horrors of Pulse don’t go away like that: death is ‘eternal loneliness,’ and the ghosts are so desperate for help that they drive others into the same loneliness. At certain points - particularly in the first hour, before a relative drop-off in creepiness - the film brings to mind Claudio’s terrifying estimation of death from Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure: ‘To be imprisoned in the viewless winds, and blown with restless violence round about the pendent world.’

Like many of Kurosawa’s movies, Pulse probably isn’t one that you’ll want to revisit very often. It takes place mostly in dank apartments, dingy hallways, and flavorless computer labs, with one rooftop garden coming like a gift from the heavens every time we get to go up there. The movie isn’t as exactingly-calibrated as Kurosawa’s Cure (1997); it’s more ambitious, so it falters more severely. (Some dated CG dust and fire; bombastic music; some didactic dialogue in the back half; an ending that verges on - and probably crosses - the ridiculous, especially with the relaxed J-rock over the end credits.) But Kurosawa is one of the only horror auteurs to emerge over the course of my lifetime, and I daresay the only one with an consistently uncanny knack for, well the uncanny: that feeling of something not being quite right, and the simultaneous feeling that something is approaching from within that state.

On a broader level, I can just quote HOSTAGEKILLER, writing on Letterboxd as torusoryu: ‘Japan knows the scariest thing ever is the computer and being sad and they knew that before anyone else. That’s what happens when your economy collapses for like twenty years straight.’

Sitting on a subway train together, one of our two main characters asks the other: ‘Where did everyone go?’ ‘I’m here,’ says the other. ‘I’m here beside you.’ And that’s the best we can hope for. The final shot of Pulse is of a boat on the ocean, carrying our two protagonists who might as well be the two last people on earth, with the frame receding so as to become an ever-shrinking rectangle. Prophetic, innit?

I mean, obviously. For that first hour.

Last hour still sucks, though.

What a tragedy that Danny Boyle fell into a coma shortly after this movie’s release. I pray for a reawakening, but it’s been 20 years now. 20 years…holy shit.

I guess. It’s not a movie that reveals anything on rewatch - well, except for the fact that the acting is a lot worse than I remembered - but it’s another film Schopenhauer would’ve loved, based on a true story of a couple who got separated from their scuba group and ended up eaten by sharks. The majority of the movie is just the two of them floating in the ocean, bickering and then falling silent, waiting for the inevitable — and looking like shit on cheap digital video.

Look: it was either this, or Takashi Miike’s idiotic One Missed Call. And I sure wasn’t picking that.

Another obvious choice. But despite Edgar Wright’s diminishing returns - the pretty-good Hot Fuzz, the excellent-in-its-first-third (before the sci-fi elements kick in) The World’s End, the empty-headed Baby Driver (which served best as an advertisement for the iPod Classic)…despite all that, Shaun of the Dead still reigns supreme as the greatest of all horror-comedies. Even John Landis’s An American Werewolf in London looks a bit pale in comparison.

Shaun of the Dead’s first 40 minutes in particular, up until Simon Pegg and Nick Frost leave their house, are pretty much perfect, affectionately setting up these very relatable layabout lower-middle-class thirtysomething dudes: badgered often about their lazy fuck-upery, yet still showing more big-hearted liveliness than the pricks and zombies that they’re expected to grow into.

Broad? Of course. But for anyone who’s ever had to work a shitty job where you get lip from a snotty dipshit kid, and then come home to forget things and still have to stand up for your lovable slob of a friend…for anyone who can relate to that, there are many close-to-the-bone moments of hilarity and even drama.

I just love how Pegg plays the scenes where he sleepwalks through the daily stupor of a zombified world. The part where he slips on blood in the convenience store and keeps shuffling through his hangover — that still makes me laugh. ‘This town…is coming like a ghost town….’

If it weren’t for the rather boring last 30 minutes, which try (understandably) to tie-up all the action and romance but doesn’t quite deliver with either - Edgar Wright has never quite been able to stick his landings - I’d call this the best movie of 2004, period. In fact, I still might. (Well, okay: best English-language movie. Jia Zhangke’s The World and Ousmane Sembène’s Moolaadé still best it on the international scale.)

My actual answer is, ‘Nothing.’ Because I couldn’t find anything spook-adjacent from 2005 that was completely or even 70% successful on its own terms. Even Jaume Collet-Serra’s House of Wax - widely disparaged at the time for the stunt casting of Paris Hilton, now recognized as harmless fun - takes too long to get going, lacks interesting villains (give me the killer telekinetic puppeteer in David Schmoeller’s 1979 Tourist Trap!), and has a terrible ‘00s rock soundtrack. (Paris Hilton, Chad Michael Murray, Jared Padalecki, Elisha Cuthbert…such relics of their age, you can’t wait to see them all bite the big one. It’s just a shame that Vincent Price wasn’t around to roast ‘em himself.)

Noroi: The Curse, meanwhile, is a Japanese film that takes the form of an amateur documentary being made by a supernatural investigator. The actual plotting is pretty murky and uninvolving, especially with all the perspectival shifts: sometimes we’re in his footage, sometimes we’re on a psychic TV game show, which would be fine if they all weren’t so haltingly and melodramatically framed with time- or date-stamps. There’s also a synth soundtrack that’s sometimes effectively glaring but sometimes just sounds corny.

What makes the movie memorable is its last half-hour, when things do start to feel ‘real’ in a more visceral way: namely, some good old fashioned demon possession! Featuring a mountain of wriggling fetuses (didn’t think I could get two fetus-horror things on the same list), a bludgeoned child with his head taking the form of a devil, and a woman setting herself on fire!

A mockumentary wherein a slasher-to-be is interviewed while he plans his dirty work. Sounds tiresome, I know. Sounds like another winking meta-movie in the Scream mold — or, earlier than that, the There’s Nothing Out There (1992) mold. And when Behind the Mask actually becomes the slasher movie it’s been teasing, in its last third - and it does just outright become it, right down to the formal qualities: no more jokes, no more handheld camerawork - it’s heartbreakingly generic. (And even if that was ‘the point,’ the point isn’t strong enough. Especially since we never even return to the documentary angle!)

But while Behind the Mask fails at horror, it triumphs at meta-horror comedy: unlike Scream, it’s actually funny, because its characters aren’t just pointing out the most obvious beats. The interview framing actually allows them to elaborate on ideas that are played for laughs, but are actually pretty straight-faced as theory. When the titular Leslie Vernon, the killer-to-be, describes the bedroom closet as a ‘sacred place’ that’s ‘symbolic of the womb,’ or that the ‘final girl’ eventually has to wield a ‘big, long hard’ weapon - taking his manhood to empower herself - it’s played for laughs, but those are not too far off from the kinds of things Carol J. Clover said in her book Men, Women, and Chainsaws (the text where the ‘final girl’ archetype was first discussed, and one of the few books of film criticism that’s actually entered the popular consciousness). Hell, I’ll have to revisit Clover’s book — she might even say those things directly.

Filmed in and around Portland by Scott Glosserman, who somehow hasn’t made anything since, Behind the Mask features bit parts from Robert Englund (amusingly, playing the Donald Pleasance role from Halloween) and Zelda Rubinstein (the medium from Poltergeist), and is held together by a charming comic performance from Nathan Baesel as Leslie, an affable bro who studies illusionists (reading hardcover books by Harry Houdini and David Copperfield) in order to make his getaways seamless. (‘I only keep pets I can eat.’) The rest of the cast isn’t very interesting, but they sure beat those people from The Cabin in the Woods.

‘The closet is a sacred place. It’s symbolic of the womb. It’s the safest place to be, because in the womb, we’re innocent.’

‘So does that mean you’re pro-life, Leslie?’

My serious contenders for 2007 were the pretty-good Spanish found-footage movie [REC] (remade in America as the dumber Quarantine) and Tim Burton’s Sweeney Todd (still his only especially good movie since Ed Wood, alas; the man does still to some extent connote ‘cinematic Halloween’ for me and so many other ‘90s kids)…and this animated French anthology movie.

There are four main stories by four different animators, along with some interspersed morbidity from the renowned French comic artist Blutch (with a skull-faced man unleashing his wild dogs on unsuspecting passerby) and some geometric Rorschach-y bits that shouldn’t’ve been there at all, narrated by some anonymous woman fretting about her political will. (‘I’m afraid I would be an incorrigible bourgeois.’ Yawn!)

The first two stories are of very mixed quality. The insectival body-horror one from Charles Burns (of Black Hole fame) looks pretty good: at one point, the starry glint in a pupil is withdrawn to contort into a tree-line in a dying man’s vision. But when you’re left to think about anything deeper, you’re just left with some casual misogyny and some grossly overly-whispered narration. And Marie Caillou’s anime-inspired one about a girl haunted by a samurai is best left muted and used as background imagery while you prepare snacks.

The last two stories, though, are sublime. Michael Koresky in Reverse Shot aptly compared Lorenzo Mattotti’s segment to the eerie picture books of Chris Van Allsburg (Jumanji; The Mysteries of Harris Burdick; The Polar Express); it’s a hauntingly ambiguous recollection of the disappearance of a child’s friend, and though the story is vague and drifty, the images are stunning, peaking in an unnervingly beautiful sequence of a crocodile being suspended from a church.

Richard McGuire’s close is a wordless haunted house story, with a man seeking refuge during a blizzard and being met with..well, just spare shafts of light and a mysterious backstory to this house that he and we are only tentatively hinted at. There’s a delightful moment where a bottle of wine falls from the man’s sleepy hand, its label rolling away to double as a ‘dripping off’ into nightmareland.

I bet that if Fear(s) of the Dark had led with those latter two segments, it’d be a lot more talked-about than it is.

When I hear the phrase, ‘a horror movie about grief,’ that’s when I reach for my revolver. But this one really lingered.

It’s an Australian movie, framed as a mid-budget TV documentary about the haunting of a family after the drowning death of the young daughter, Alice. The remaining child places cameras around the house, and unwittingly ends up recording images of Alice simply lingering in the background, staring into the camera.

What it feels like is a TV documentary about ghosts that happens to have been cut and scored by someone who sees this family’s grief and identifies all too well with it. (This makes all those B-roll TV shots, where the camera just looms into an empty room, genuinely scary in ways those TV ghost shows usually don’t.) There are twists and turns in the actual narrative - involving Alice’s secrets - that feels something like the unpredictability of real life, and there are offhand remarks from the family that cut right to the bone in terms of how people deal with a child’s death: the father admitting that he hoped the body would’ve been ‘anyone else’s kid’; saying that they were glad to find the first lingering image of Alice because ‘It gave us something to focus on.’

Most movingly of all is a scene where the mother reads one of Alice’s diary entries, a scene that seems like it was scripted by someone who deeply understands the feeling of being helpless and on the brink. ‘Then the sadness turned to fear. I just stood there paralyzed with fear, and I realized there was nothing that they could do for me any more. I’d never felt so utterly alone. Everything felt wrong. My body. The way things looked. Then I realized there was something wrong with me.’ This recalls the confession of another dead young girl who shares Alice’s surname: Laura Palmer, in Twin Peaks; specifically, the scene in Fire Walk With Me (1992) when she talks about openly and willingly going into the darkness, because nobody can help her anyway and she’s no longer going to try to help herself.

If this all sounds too grim, rest assured: it’s fucking scary, too, never moreso than in a scene toward the end, in a piece of cellphone video that really did - and I don’t use this phrase lightly - chill my blood. In a few waves, actually. Lake Mungo is one of the better films on this list — and to me, aside from The Blair Witch Project, the scariest.

I reckon I don’t need to rehash the story for this one — everyone’s seen it. But it really is sublime, and fits the misty late-autumn air so snugly that it feels like a Halloweeny movie even if the date is never even mentioned.

Apparently it was absolutely mind-busting in 3-D. As Eileen Jones of The Exiled pointed out, for Nightmare Before Christmas and James and the Giant Peach director Henry Selick, 'designing for 3-D seems to have driven him into a wonderful, spacially obsessed fugue state in which you'd swear he's theorizing at a very high level on the history of representing depth of field in various art forms for two hundred years. You've got your diorama effects, your 19th century theatrical trompe l'oeil backdrops, your pop-up books, your 1930s-'40s Disney experiments in 3-D effects with the multiplane cameras, and so on, all evoked and alluded to throughout. Spaces in the house keep expanding and contracting, sinkholes open up, characters shape-shift, round orb-eyes are opposed to flat button-eyes, it's so detailed it's maniacal.’

I've only seen it in 2-D, alas. But Selick and his team are such mad geniuses that those impressions still come through. The figure designs aren’t as bizarrely memorable as the ones in A Nightmare Before Christmas (maybe credit animator Paul Berry, who made the terrifically Halloween-appropriate short The Sandman and collaborated on Selick’s first two films), but still: nothing really looks like this. Not even the other Laika movies, the next-best of which I’ll soon get to. Nothing quite sounds like this one, either, at least in the case of some of Bruno Coulais’ music; honestly, when I think of the movie's power I think first of that scene where a bored Coraline wanders through her new house, counting doors. The piece of music that soundtracks that sequence - arranged for harp and voice and titled “Exploration” on the soundtrack - is such a loomy, haunting, deeply catchy October of a melody, touching a foggy-day zen that fits perfectly with the setting: it’s waking up in a different place; it’s a bump in the rug that just won't go flat; it’s narrowing hallways narrowing eyes; it’s witchy flowery breath unspooling through a secret dream-door. Sometimes I find myself humming that tune absent-mindedly for hours at a time; it’s always calming, always humbling, casting off so much of life’s nonsense and putting me just slightly outside my body — in that way one might experience if they start to glean that nothing really matters. Like the film, it evokes spooky old-world childhood feelings in a way that could only come from the minds of adults looking back through children’s eyes.

Neil Gaiman’s source novella is brisker than the movie, which ebbs in and out of tension and/or conflict in odd places toward the end — not always to its benefit. The climactic ‘game’ is sorta shuffled-through, and the lost eyes/trapped souls parts worked better in the book. (Those ghost voices are a bit too sickly-sweet here.) I could also nitpick the ever-so-slightly ‘rounded-off’ quality to the human faces; I’m partial to the knottier grotesqueries of the Nightmare Before Christmas figures. And the addition of oddball boy-crush Wybie, who wasn’t in the book, while not bothering me as much as it probably should, does diminish some of Coraline’s own cleverness and decision-making at the very end.

Moreover, the voice of Coraline frankly could’ve been cast with more imagination. I like Dakota Fanning fine, and can’t blame the studio for wanting a bankable star’s voice to help sell a project they put this much work into. But I still wish the voice could’ve been a little quirkier, a little deeper.

On the other hand, though, the whole ‘point’ of Coraline is that she isn’t some dull goody-goody kid-lit cypher with a moralizing ‘lesson’ to her story — she’s more like a lot of the actual children of overworked Gen-Xers: snarky, temperamental, skeptical often to the point of rudeness…but with a hunger for games. Eventually, we do start to feel a real kinship and even loyalty to this spindly, precocious young girl as she wanders through her spooky surroundings under an old military cap — there’s a bit of a Calvin and Hobbes energy there. Coraline becomes one of the few sources of color in a world that seems leeched of its liveliness, or at least with its liveliness operating on a darker subconscious level that Coraline is only just starting to discover. This culminates toward the end with an entrance into white limbo space with the mischievous black cat (voiced by the great Keith David), and later the apocalyptic image of the door to the Other Mother rapidly hammering its way toward her — truly nightmarish!

2010 was so barren for good horror movies that I’m choosing a documentary about 1980s horror movies. (Seriously, what else was there? I Saw the Devil? A Serbian Film? No.)

This is a standard but mildly illuminating doc about the ‘Video Nasties’ phenomenon, a moral panic in the U.K. that effectively blacklisted 72 films from distribution and put many others in similar company. That list of 72 included many pieces of hateful sleaze (not that that should’ve been censored either, of course), but it also included a lot of films that are now justly recognized as classics: Matt Cimber’s The Witch Who Came from the Sea (1976); Tobe Hooper’s Eaten Alive (1977), Abel Ferrara’s The Driller Killer (1979); Dario Argento’s Inferno (1980); Jess Franco’s Bloody Moon (1981); Lucio Fulci’s The Beyond (1981); Andrzej Żuławski’s Possession (1981)…Christ, what the hell did people do for fun in Thatcher’s England?

My biggest gripe with the doc, other than its merely tepid political points and its lack of formal invention (sadly a standard complaint for most docs made over the last 20+ years), is the fact that director Jake West doesn’t include enough of the critic Stephen Thrower. He’s in it for a bit, but not nearly enough; I mean, who knows more about this era and material than Thrower, whose great 2007 book Nightmare USA is the quintessential text on the whole milieu of exploitation independents?

But it’s a good introduction to the subject, and it does have a few tidbits that I didn’t know, my favorite being that Samuel Fuller’s batshit-crazy (and pretty great) WWII drama The Big Red One (1980) was mistakenly shortlisted as a Video Nasty, because the British censors assumed it was a violent porn movie!

Anyway, even though I didn’t live through the Video Nasties era, Jake West’s documentary took me back fondly to memories of Friday nights spent perusing my dearly departed Showtime Video, which reeked of tobacco smoke and was staffed by layabout teenagers who had no qualms about renting R-rated horror movies to a 10-year-old.

A ghost movie that even your grandmother might enjoy. It’s about two very likable young-ish people pulling the all-night shift in the waning days of an old New England hotel that’s rumored to be haunted.

As with director Ti West’s The House of the Devil (2009), The Innkeepers is a ‘slow burn,’ classical really, and the scares that do come are often ‘boiled to unavoidable suggestion’ rather than shown outright. For the most part, it’s just a fun spooky hangout movie: we follow the adorable Claire (Sara Paxton) as she kills time on her shift with some amateur ghost-busting and occasionally interacts with the hotel’s few odd guests. Unlike Jocelin Donahue’s rather impudent ‘babysitter’ in The House of the Devil, Claire and her coworker Luke (Pat Healy) are people whose company you might actually like to keep (‘Idon’twannascareyoubutI’mstandingrightbehindyou!’).

The movie’s spookiness comes from wondering where the threat will end up coming from. Upstairs, with those few strange guests? The main floor, with its creepy piano room? Or maybe that ominous basement where the body of a jilted bride was stowed away 200 years ago?

Ironically, where House of the Devil built to a pleasurably ghoulish finale, The Innkeepers kinda fizzles out in its last five minutes — they’re a downer, actually. But I guess sometimes one has to follow horror to its logical conclusion in order for it to remain horrifying. And even there, the movie ends with a closing shot that features some of the subtlest on-screen movement I’ve ever seen — I had to rewind it three times before I saw what I was supposed to see!

Laika’s follow-up to Coraline lacks the Genius Factor of Henry Selick, and our zombie-loving outcast hero Norman is a bit too much of one of those ‘adorable misunderstood cuteboy’ types that nevertheless feel market-researched to a tee — unlike the disagreeable Coraline. But ParaNorman is just as wonderfully seasonal as the Selick film. The story is a fun little romp about cursed zombies coming back to haunt a small town for its Puritanical witch-hunting past, but what stands out most is the detailing of that town. This isn’t a squeaky-clean Pixar city that’s filled with agreeable adult authorities; this is a town that clearly survives on scant tourist dollars, filled with dead grass and dilapidating houses and chain-link fences and cranky, overworked parents.

I’d say that kids could probably relate better to that milieu than they could to a movie where the people are cars…but then again, what the hell do I know about those little bastards?

Comedian Bobcat Goldthwait’s Blair Witch Project knockoff, wherein a hot young couple of dippy thirtysomething professionals, on a lark and for an excuse to vacation, go off into the northern California woods for a few days to find Bigfoot.

Unlike some of the other recent instances of comedians doing horror movies (Get Out; the 2018 Halloween), Willow Creek isn’t funny, and it doesn’t really try to be. Or at least, I hope Goldthwait wasn’t trying; I certainly never cracked a smile. Unless that one lame ‘calling attention to the cliché in a vain attempt to expunge the cliché’ bit (‘No cell reception…beginning of every horror movie’) was supposed to be a hoot.

(What’s actually funny is that one of the two Blair Witch Project directors, Eduardo Sánchez, ended up making his own found-footage Bigfoot movie, Exists, the next year. Not particularly recommended.)

2013 is another year where I thought I’d come up empty-handed for a good horror movie, but what puts Willow Creek over the edge is a laudably patient shot in a tent that comes at least two-thirds of the way into the movie: we just watch the couple as they listen ever-more-closely and react to the weird knocks and moans that keep getting closer. That shot holds for 20 minutes without getting boring! So that’s enough for me. And the actual payoff is…well, good enough.

Freud’s return of the repressed, in dark-ambient-shoegaze form!

This is another one you already know the gist of, so I won’t explain it. It’s one of those movies that I kinda wish I hadn’t seen more than once, though: every time I see it, it gets a little less satisfying. And I don’t think that’s just the natural tendency of horror movies (or anything) to simply lose the elements of surprise on repeated viewings. It’s just that what was already problematic the first time seems dumber each subsequent time. The visuals of the invisible figure whipping someone across the beach - or whipping things into the swimming pool - were always pretty silly, and I can’t imagine anyone being satisfied by that swimming pool climax in general. Why does the ghoul fall down when it gets shot — shouldn't it just, um, keep following? Wouldn’t that be both scarier and also lessen the inevitable questions about its physical logic? And why are all the girls wearing short-shorts in autumn? And let’s not even go into the ambiguous scene where Jay swims out to the jocks on the boat, which I’ve heard many theories about but haven’t met anyone who thought it was successfully-executed in any of those intentions.

And yet it’s a fool’s errand to argue with the atmospherics here, which alternate between gorgeous dreamy calm and a deep-throbbing dread that was then still unusual for the typical retro-‘80s horror-movie fumblings. Though It Follows isn’t set in the ‘80s, it nevertheless evokes an imagined 1980s young adult world that was, as implied here, always teeming with anxiety within the daydreamy-ness. The ominous thrumming John Carpenter-y synths and creepy-crawly dripping-faucet plucked strings on the soundtrack (by Disasterpiece) are expertly matched to those feelings: just witness the rhythmic pauses in the score during the scene where the kids go to a school to look at yearbooks, where the pauses force you to scan the screen nervously while the camera spins slowly around and around. (A later hospital scene, where our main character is confined to a bed and hears footsteps coming down the hallway, her breath getting closer on the soundtrack, is a real goodie.) Director David Robert Mitchell makes ordinary houses and schools seem incredibly forbidding, and actually the most immediate problem with the movie is that it’s never quite as creepy after they leave the suburbs for the first time. The movie’s conceit does ingeniously allow us to be taken to a variety of locations - from suburbs to beachside to slums - but the suburban scenes are the most memorable, with some nightmarishly beautiful compositions: a shot looking in on the window above the four plastic chairs outside; the beach against the dark sky at the beginning, cutting abruptly to a grotesque Salvador Dalí Boiled Beans shot; a hypnotic expanding of light as we emerge from a highway overpass.

And some scenes are just beautiful with no qualifiers of horror at all: the pastel-bleary scene of our lead girl getting ready for a date in front of her mirror; the voyeuristic dreamworld conveyed in a backyard swimming pool. And though it’s already become obvious to point it out, I don’t remember a horror scene in the 2010s that yielded a more of powerful ‘stomach-dropping-out’ moment than that image of a tall sunken-eyed man leaning through a bedroom doorway.

If hell is other people, horror is something coming.

I mean, it does kind of suck that one of the better horror movies of the last decade had to fit into the category of so-called ‘elevated horror.’ (The closest thing to a runner-up in 2015 was M. Night Shyamalan’s The Visit, still the only good movie Shyamalan’s made since The Sixth Sense.)

Set around 1630, several decades before the Salem Witch Trials, The Witch opens with a Puritan family - a father, a mother, a young teenage daughter, a pubescent boy, two fraternal twins (very creepy as twins, like two old women in small bodies, but without the movie making a big conscious show about them being creepy), and a newborn baby - being defended by the father in some sort of deposition. The father refuses to apologize for preaching the Gospel with, apparently, too much fervor even for the Puritans, and the family is banished from the settlement. So we’re out the doors within the first two minutes of the movie - it’s a slow burn, but that's not to say it’s slow; on the contrary, it's a pretty tight 93 minutes - and in a great offhand detail we see an indigenous person pass by in the settlement as the family’s wagon rolls out. This forces us to wonder: ‘What the hell could this father have said if even the natives are more welcome in this colony than he is?’

Shot mostly with natural light (and candlelight), writer-director Robert Eggers’ movie has a stark, ashy palette and a knack for showing austere Old World faces under tremendous pressure. This land is uninhabitable, the forest an endless sea; these über-Puritans view God’s love and wrath as hostile, and as something to be earned; thus, brute nature and encroaching paganism meets them on their own terms.

I’m always surprised by how early the family lose the baby, and how unsettling that sequence is where we see a succubus with mortar and pestle grinding up the baby flesh — as an incantatory violin saws and churns on the score. (Striking imagery of blood on straw.) And yet the scariest scene in the movie isn’t even any of the witch-related ones, though of course there are other memorably disturbing images in that vein. (The crow picking apart the breasts of the mother as she laughs madly away, hallucinating; the ending sequence, even if I wish they hadn’t tried to show the devil.) Rather, it’s the scene where the children, their faces all still and worried, simply hear their mother crying in the next room late at night, despairing that ‘We will starve!’ The fear that your family - the only authorities you know who are capable of protecting you in this environment - are on the path to defeat, to a death as pitiful as starvation at that...yeah, that’s true fear.

Much is made from both fans and foes of this film that the dialogue is all spoken in the original, now-arcane dialect of the actual Puritans. I thought Eggers’ attempts at doing Herman Melville (or Melville-era) language in The Lighthouse (2019) often crossed over the line into outright purpleness; the movie was fun enough while it played, and I certainly appreciate the visual ambition, but it’s a movie where no true terror is ever conjured, because the authorial gears are so obviously and deliberately trying to work us over. But in The Witch, the dialogue feels apt and unshowy. ‘If not a wolf, then hunger would’ve taken him yet’ is a memorable line. ‘There must be some fruit yet untouched by this rot’ is another.

Anya Taylor-Joy, as the eldest (and to the rest of the family, most suspect) daughter, is just okay; her chops aren’t up to the heavy lifting required in a few scenes. Conversely, Ralph Ineson and Kate Dickie as the parents are fucking phenomenal; Dickie in particular probably didn’t get enough credit, but she perfectly establishes a mother figure who is truly inconsolable: it’s clear she’s lost her faith and can’t admit it — even when she finally (basically) does. (In that confession scene, she also admits that she wishes she were back home — not in the colony they were banished from, but in England, and you're forced to realize again how godforsaken and uninhabitable this land must've seemed to newcomers; how it would’ve put even the strongest faith through the ringer.)

For this family’s pubescent son - seemingly the most innocent member of the family, apart from the baby - to be taken from them midway through the film is scary, but what’s scary and even sort of insightful is the mesmerizing scene where he dies, vomiting up an apple and then reaching what seems to be an almost sexual transcendence ‘into the lap of salvation’ before expiring. That scene would be unnerving enough just for that, but what makes it fascinating is the (appropriately) horrified reaction of the family, which I read as: Even when they witness someone who really does seem to be approaching a transcendent God, and appears to have been lifted into the Kingdom of Heaven...even then, the alleged believers can’t love it; they can’t understand, which just goes to show how thin their faith really is.

A big-budget 146-minute box office bomb! I can’t honestly claim this is even necessarily a successful film — but if it’s a failure, it’s a grand one, made by a blockbuster director who used all his spoils to make The Lone Ranger (2013) and this big-budget Roger Corman exploitation movie. (He’s been in Director Jail ever since.)

Gore Verbinski’s ambition is under-sung: when he succeeds (Rango; parts of his Pirates movies), he succeeds in a way that, as Eileen Jones of Jacobin was the first to point out, marks him as one of the only contemporary filmmakers who could’ve survived and thrived in the Benzedrine go-go American studio system of the 1930s and ‘40s. And when he fails (The Lone Ranger; A Cure for Wellness), he fails in fascinating and spectacularly ambitious ways.

Also, I just want an excuse to say it: Verbinski’s American Ring is better than the Japanese one. Of course Hideo Nakata’s Ringu is the more interesting historical artifact - it got there first, and helped kick-off the crossover appeal of that aforementioned wave of tech-conscious ‘J-horror’ in the late-‘90s/early-‘00s. Plus it’s not as though Gore Verbinski doesn’t follow most of Nakata’s story beats and visual templates. But what freaks me out about Verbinski’s Ring - what comes to mind when I think of the movie - isn’t the notion of a ghost coming out of my TV (which, no, doesn’t scare me), nor even of that pale creepy girl herself. It’s not even that early jump cut to the dead girl in the closet and her hideous decomposing face. It’s the overcast vibe, especially during the sequence where Naomi Watts and the other guy go to that girl’s house and uncover the well. At that point, all the video’s weird imagery starts to resurface in your mind’s eye, and it conjures some deep sinking-feeling dread even before Watts’ annoyingly creepy little kid tells her that she did wrong.

A Cure for Wellness, meanwhile, stars some guy named Dane DeHaan as a young financial executive who’s sent to investigate the disappearance of the CEO, who broke contact during a retreat to a mysterious ‘wellness center’ in the Swiss Alps. ‘I am not a well man,’ he says in his letter urging them not to contact him.

This all has a vague Night of the Demon (1957) or Messiah of Evil (1973) vibe to it, appropriate to a mash-up cinephile like Verbinski, and I’m not gonna get much further into the plot — as if I could. But I’ll say this: in that nutty ‘Roger Corman’s Grand Guignol’ sort of way, A Cure for Wellness ends up involving mysterious medicines, swarms of eels, tainted water, creepy scientists, and - in a too-tasteless-but-admirably-out-there twist - incestuous rape from head doctor Jason Isaacs.

A Cure for Wellness is either a grand failure, or a success qualified with the weight of a thousand pounds of other exploitation movies that got too big for their britches (and of course weren’t afforded such a budget). But it’s ghoulish, mysterious, and has a lot of memorable imagery! And it’ll take years before the future vulgar academics might be able to diagnose how successfully the movie ties ‘corporate sickness’ in to familial abuse and environmental conspiracy.

If it’d had a more charismatic lead actor, I’d be a lot more confident about it becoming a cult classic.

The one that’s Groundhog Day played as a slasher. A university student keeps re-living the same day, always murdered by a baby-masked killer, until she can find out who’s behind the mask.

I always want to like Blumhouse movies more than I do. This one’s okay. The mystery did succeed in fooling me. Can you tell I’m desperate here?

Featuring a long-overdue instance of death-by-bong.

A video-messenger horror movie, and an improvement on the original Unfriended (2014) by implicating the internet-addled audience in its (our) complicity.

…Not complicity in black-market skull-drilling, mind you. But, y’know…complicity. In the general dumbening.

‘The kicker image is a pull-back reveal that locates the screen that we’ve been watching in a larger, crowded field of chat boxes and tickers giving up-to-date odds on the outcome of the unfolding decimation of Matias and his friends, a spectator sport set-up whose ultimate result was never really in doubt. Like the conclusion of Oliver Assayas’s 2002 demonlover, it shifts our perspective from the production to the consumption of forbidden images, in the process pulling off a combination of technophobic warning and nasty implication of the audience and Internet culture as a whole. Earlier the film had established its key image, that of a fathomless mise-en-abyme, when a Circle member turns the screen of his phone so that Matias can see it, revealing that they are looking at the same screen, this creating an image of screens within screens in perpetuity. By this point we’ve completed the transition from the middlebrow nihilism of Cards Against Humanity (“a party game for horrible people”) to the real thing, a game night conducted by horrible people amusing themselves by monetizing human suffering.’ — Nick Pinkerton

Another year where I almost just said, ‘Nothing.’ Jim Jarmusch’s latest toss-off is not scary and might not even qualify as ‘good.’

But I find Jarmusch’s recent turn toward horror archetypes - vampires in 2013’s Only Lovers Left Alive, zombies in The Dead Don’t Die; amateur poets in 2016’s Paterson (I josh, Paterson’s still his best since Dead Man) - to be rather fascinating, especially from someone of the aging punk generation.

In The Dead Don’t Die’s ‘vacuum of inertia’ (to quote Reverse Shot’s Jordan Cronk), we mostly follow three small-town cops (Bill Murray, Adam Driver, and Chloë Sevigny) as they gradually start to realize that the days have halted and the dead are rising. Jarmusch always nets great ensembles: Steve Buscemi as a white-supremacist farmer, Danny Glover as an auto mechanic; Tom Waits as a survivalist, Selena Gomez as a traveling college student (Gomez would vie with Robert Pattinson and Kristen Stewart as our resident ‘teen performer once mocked, but who’s now working with important auteurs’…if only she were a more interesting performer); RZA as a UPS delivery man; Iggy Pop, Carol Kane, and Sturgill Simpson (who performs the maddeningly repeating title song) as zombies; Tilda Swinton in a particularly dumb role as an undertaker with a sword.

It’s not a particularly funny movie, except for one part where Steve Buscemi steps out of his house and goes: ‘Holy shit! Who stole my fuckin’ cows! And where the hell are my chickens?’ There does always seem to be something of a safety net in Jarmusch’s movies, no matter how violent they may get — or at least, when people do die it leaves no emotional impression. (Jarmusch is similar to Wes Anderson in that way, and both directors can sometimes get on my nerves for similar reasons.) And I do maintain that Jarmusch’s best films are the black-and-white ones: Stranger Than Paradise (1984) (whose Eszter Balint makes a heartening return here), Down by Law (1986), and Dead Man (1995), with 2003’s Coffee and Cigarettes being one of his many slighter efforts.

Partway through, Adam Driver’s character even admits that he knows how the movie’s going to end, because he read Jim’s script — a gimmick that makes the movie stand out a little more, but which also feels like Jarmusch acknowledging that he just sorta coasted his way through a screenplay.

Plus, all the stuff with the teens trying to break out of the detention center is snoozeville.