The penultimate 10. Now we’re getting into the real heavy-hitters.

Let’s just take a moment to reflect on how well Miles Davis used his own name. The Musings of Miles…Miles Ahead…Milestones…Miles Smiles…Miles in the Sky…one of the cats who lives in my house is named Miles, and he’s rarely that clever.

Also, fun fact that I didn’t have room to put anywhere else: in October of 1969, Miles and Jimi Hendrix reached out to Paul McCartney about doing a session. Paul was on vacation - this was about a month after Abbey Road came out - and didn’t get the telegram in time. There, now you can be as angry as I am.

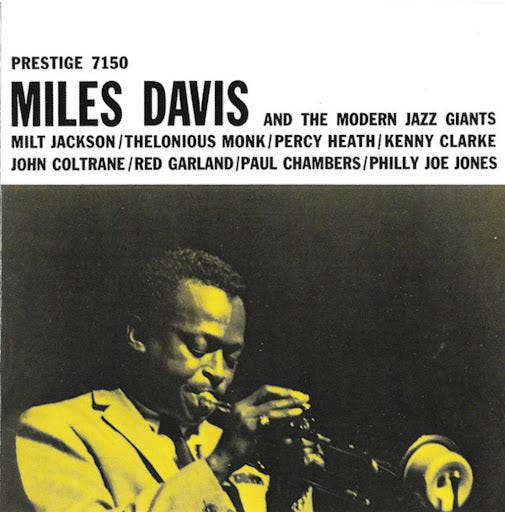

Four tracks with Thelonious Monk (piano) and Milt Jackson (vibraphone) from Christmas Eve 1954, plus a 1956 re-do of “‘Round Midnight” with the ‘first great quintet.’ It’s an EP padded with an alternate take, and “Bemsha Swing” is dry compared to the fall-outta-your-chair version Monk recorded two Decembers earlier with Max Roach. But: this drizzly-day “The Man I Love” (go with the opener, take 2) and the delightful blueberry cream of “Swing Spring” rank with the same session’s “Bags’ Groove” — superlative recordings of ‘50s jazz. These were Miles’ first sessions with vibes, and while the addition of trombone would hue 1955’s Blue Moods with more deep-sea ballast, these colors are equally dazzling in a more ‘pure and innocent’ way. Stanley Crouch on “Swing Spring”: ‘to tell Monk that he loved him, even though he wouldn’t allow him to play while he was soloing, Davis quotes some Monk licks[.] [...] The rankled giant responds by taking the lick and building an incredible solo of virtuosic colors, turns, harmonies, and rhythms that seems to say, “Excuse me, young man, but if you intend to piddle around with my stuff, see if you can get to this!”’

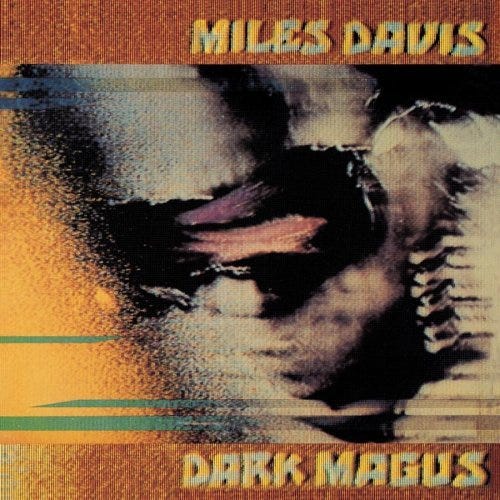

Recorded at Carnegie Hall with three writhing guitarists, this gives up all its ideas on the first disc. “Tatu”, a faster “Wili” with more of Miles leaning on his keyboard, only gets nifty in the last third of part 1 (part 2’s a doofy “Calypso Frelimo”), and “Nne” is best when noisiest. But that first disc? That is some heavy-limbered funk-rock percussion bearin’ down on ya! “Moja” is an all-time clobber-groove (Dave Liebman’s scary sax, dancing on the spot six minutes in! band stepping off so ominous and bumpin’ at 8:24, you’ll forget who you’re listening to!), and you can hear plenty of ‘90s jungle and rock-hop in this music. (“Wili”’s funky blip and cowbell is a goldmine for samplers.) Quoth Simon Reynolds, this music is ‘turbulent, closer to mob rule or a flash riot. By this point, conventional structuring principles have long since been smelted down by the infernal heat generated by the ensemble, leaving just riffs, vamps, blips and blurts of sound, and irregular escalate-and-ebb dynamics that resemble the feverish struggle between a body and a contagion[...]between spasm and entropy. In mob rule, there are no ringleaders[.]’

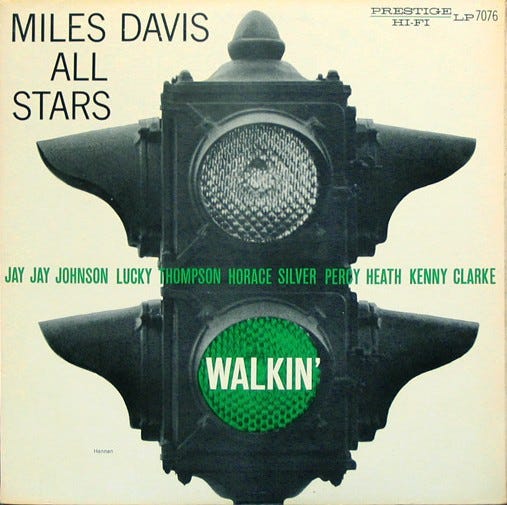

Not to be confused with the subsequent Verbin’ Quadrilogy (Cookin’, Relaxin’, Workin’, Steamin’), this gathers two April 1954 sessions: two opening tracks with tenor sax and trombone, and three others with alto and no trombone. The first two, “Walkin’” and “Blue n’ Boogie”, are seminal blues numbers, both riding the hard-bop wave as it gathered force: the former spreads out and earns its title in a way that’s almost palatial, and features an eight-bar intro with some fabulously dramatic piano flourishes from Horace Silver; the latter is more up-jump, with Silver once again a standout. Miles picks up the mute for the other three: two pleasant but minor standards, and a track called “Solar” that’s…one of my favorite things ever. Turns out Miles cribbed “Solar” from Woody Herman guitarist Chuck Wayne, but it’s a beguiling tune regardless, and features an alto sax solo (from the great yeoman Dave Schildkraut) with a tone so afternoon-breezy that it makes Stan Getz sound like a ton of bricks. This is also Miles’ first great rhythm section; as Gary Giddins pointed out, few drummers ever used cymbals and hi-hats with as much color as Kenny Clarke on “Walkin’”.

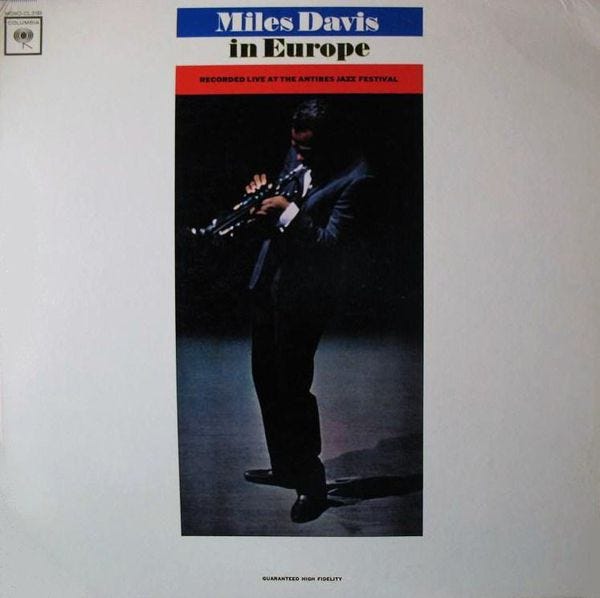

Like the same lineup’s subsequent My Funny Valentine, this is five tracks, live and long. But it’s not slow and intimate like Valentine, nor speedy (rushed) like ‘Four’ & More; it’s a happy middle, admittedly tending toward the quicker side. Nothing as poignant as Valentine’s title track, no. Herbie Hancock lifts weights to keep us interested through “All of You”’s 17 minutes, and there’s a slightly dulled quality to the mix — especially compared to the pitch-perfect Valentine. But it’s a more conclusive LP, particularly as the point where drummer Tony Williams - still a teenager! - begins his wondrous clatter. (“Walkin’” makes Miles perhaps the only musician this side of Eisenhower to preside over two different people’s drum solos that are both worth hearing.) Miles and George Coleman buzz with life in “Autumn Leaves”, and there’s a stupendous “Milestones” where every player’s in top form: Herbie increasingly punctuates the space between the repeated four notes of the head; Coleman’s bird-calls (3:30) are playful like he should’ve been in-studio. The CD adds “I Thought About You” (featuring a hilariously flabby trumpet note to halt the band’s pep…until that perks up at 1:30) and notes from Harvey Pekar!

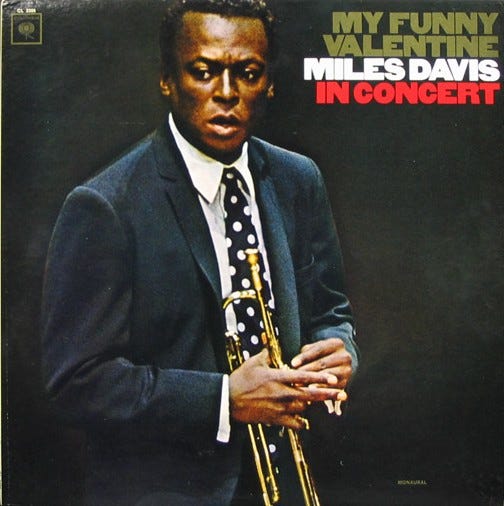

Five ballads, live and long, recorded at Philharmonic Hall in support of Southern voter registration — just days after the Medgar Evers trial deadlocked in Mississippi. The title take, particularly the first three minutes with trumpet right upfront, is Miles letting us in to that most ‘intimate self’ for one of the final times — which feels weird to say, given how much of his later music continued to pierce-through about The Human Condition™. Ron Carter’s entrance at 1:05 turns toward dread...but then, a shift - the track continues meter-shifting over 15 minutes - and 1:24-1:50 ranks with “Miles Ahead” as Miles’ most bittersweet bit of soloing, with a pause that brings hush to the air. And then...a splash of water - those victorious arpeggios from 2:51-2:58! - and the band steps out, all hitting the streets together. It’s a rare delight to hear Ron and Herbie Hancock strum-decorating all by themselves toward the end, and George Coleman did his best sax playing ever on this night. The other four cuts aren’t as revelatory but are all splendid: Miles is soused and funny in “Stella by Starlight”; Herbie shimmers nebulae. Perfectly recorded, too.

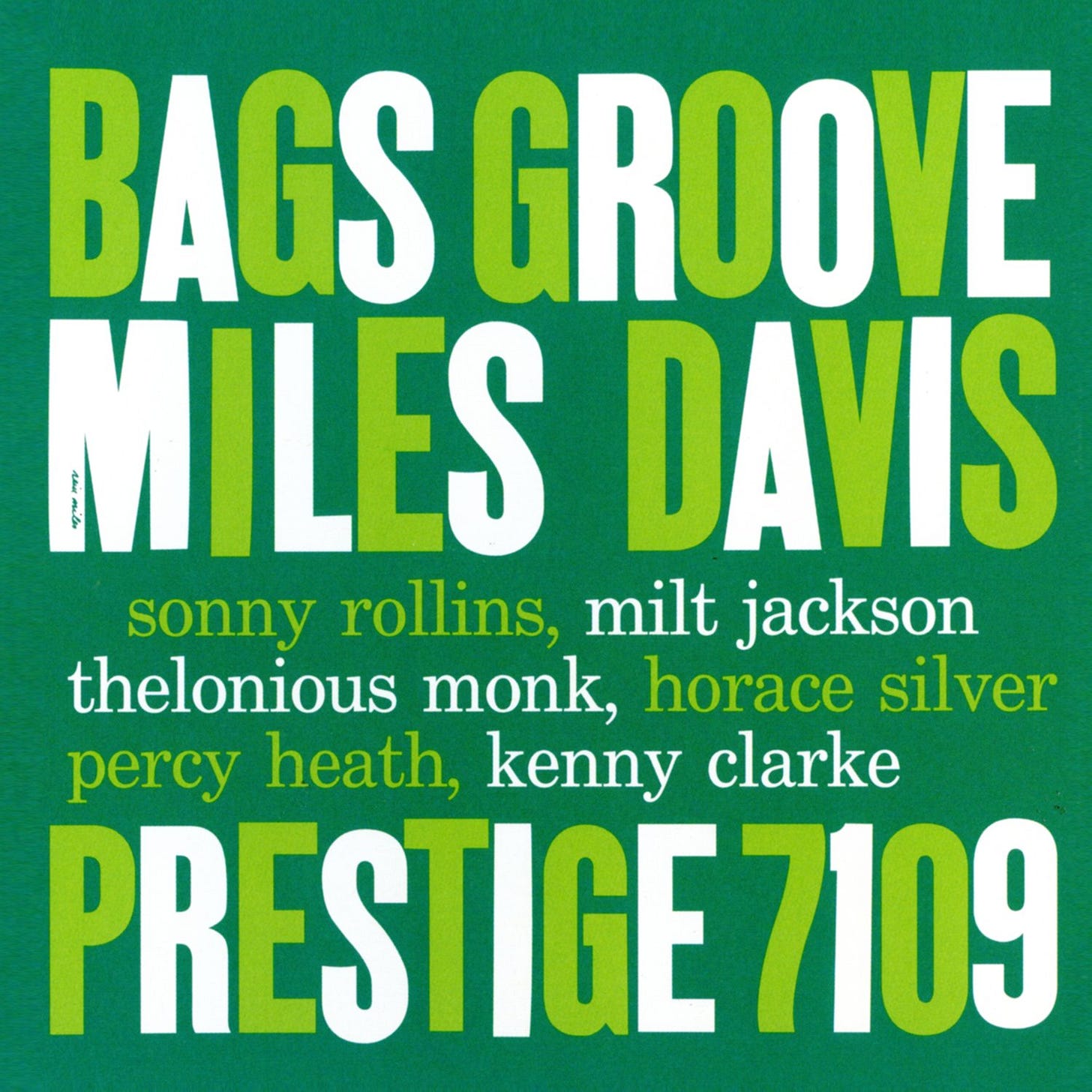

Two 1954 sessions. The title track - take 1 preferable - features Milt Jackson’s vibraphone and Thelonious Monk’s piano, and is probably the definitive piece of vibes-jazz: a slinky kitchen mellow, hazy with offhand imagination from every sous chef. Miles’ pause-for-a-flourish (around 3:00) is the type of casually lovely bit of melody-making that would soon cross him over, and Jackson - who’s on Jazz Vibes’ Mount Rushmore with Hampton, Norvo, and Hutcherson - tickles noony blue-glass heaven around 4:35. (Plus, catch Monk quoting his own gently-climbing “Misterioso” riff at 7:15!) The four other tracks - with two takes of Gershwin’s “But Not for Me”, the longer 1 preferable - swap Monk for Horace Silver (you could do worse) and vibes for Sonny Rollins, who debuts three of his most major compositions: “Airegin”, “Oleo”, and “Doxy”. This “Airegin” sounds tame against the sizzle that Miles would cook with Coltrane two years later, but it’s churlish to complain when we’re blessed with both (Kenny Clarke kills those rolls!), and this “Oleo” remains my favorite: Miles, soft and skippy; Rollins, a breeze; Silver, finally standing out; Percy Heath, holding the whole show together. (This bass mix is an ideal.)

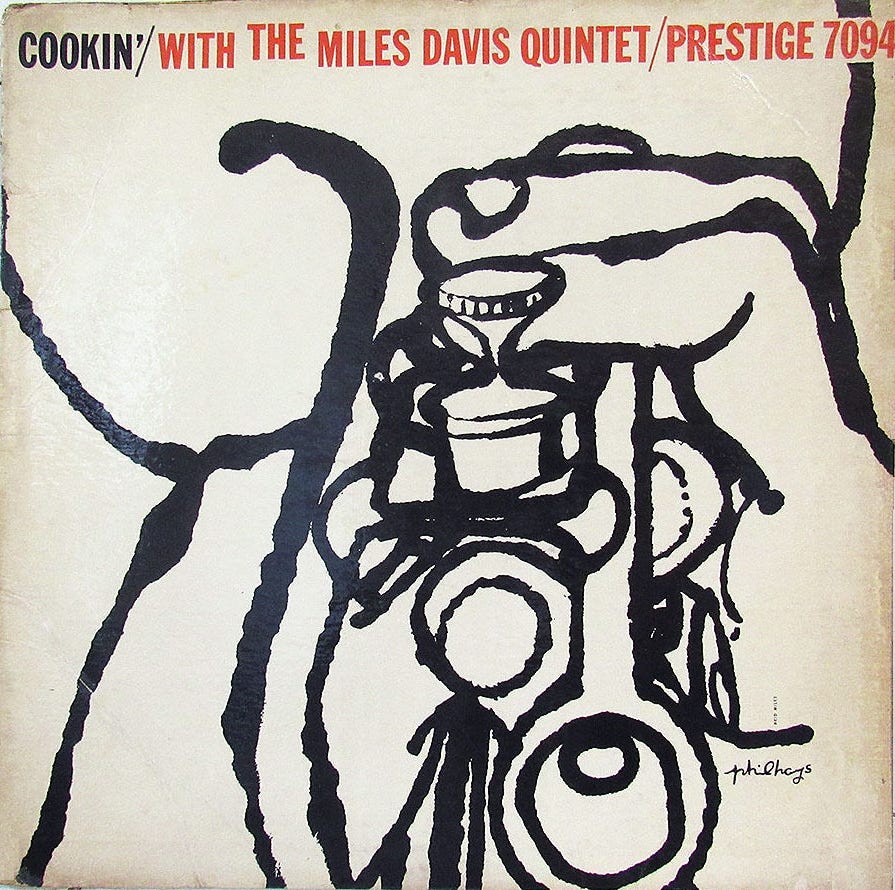

The first and possibly best of the Verbin’ Quadrilogy, four albums (Cookin’, Relaxin’, Workin’, and Steamin’) recorded over two days on either end of 1956. Cookin’ is drawn entirely from the second, superior session, and opens with a famous version of Rodgers and Hart’s “My Funny Valentine” that remains one of Miles’ most beloved recordings. For good reason, too: it’s almost impossibly delicate, with a candy-winsome piano intro and the rhythm section intermittently tickling the tempo while Miles coifs his aches. It’s probably the very first track I’d play for someone who asked for a representative example of Miles Davis’s trumpet playing. Sonny Rollins’ “Airegin” is even better here than it was when it debuted two years prior with Rollins himself: it’s a rush of sizzling-hot energy, with Philly Joe Jones cooking up a storm on the drums. The long closing ‘medley’ is just okay, but “Blues by Five” boasts a delightful Red Garland piano solo (and some dynamic fills from Jones toward the close) and “My Funny Valentine” and “Airegin” are both stellar enough to rank this album pretty damn high. It’s almost too easy to take it for granted!

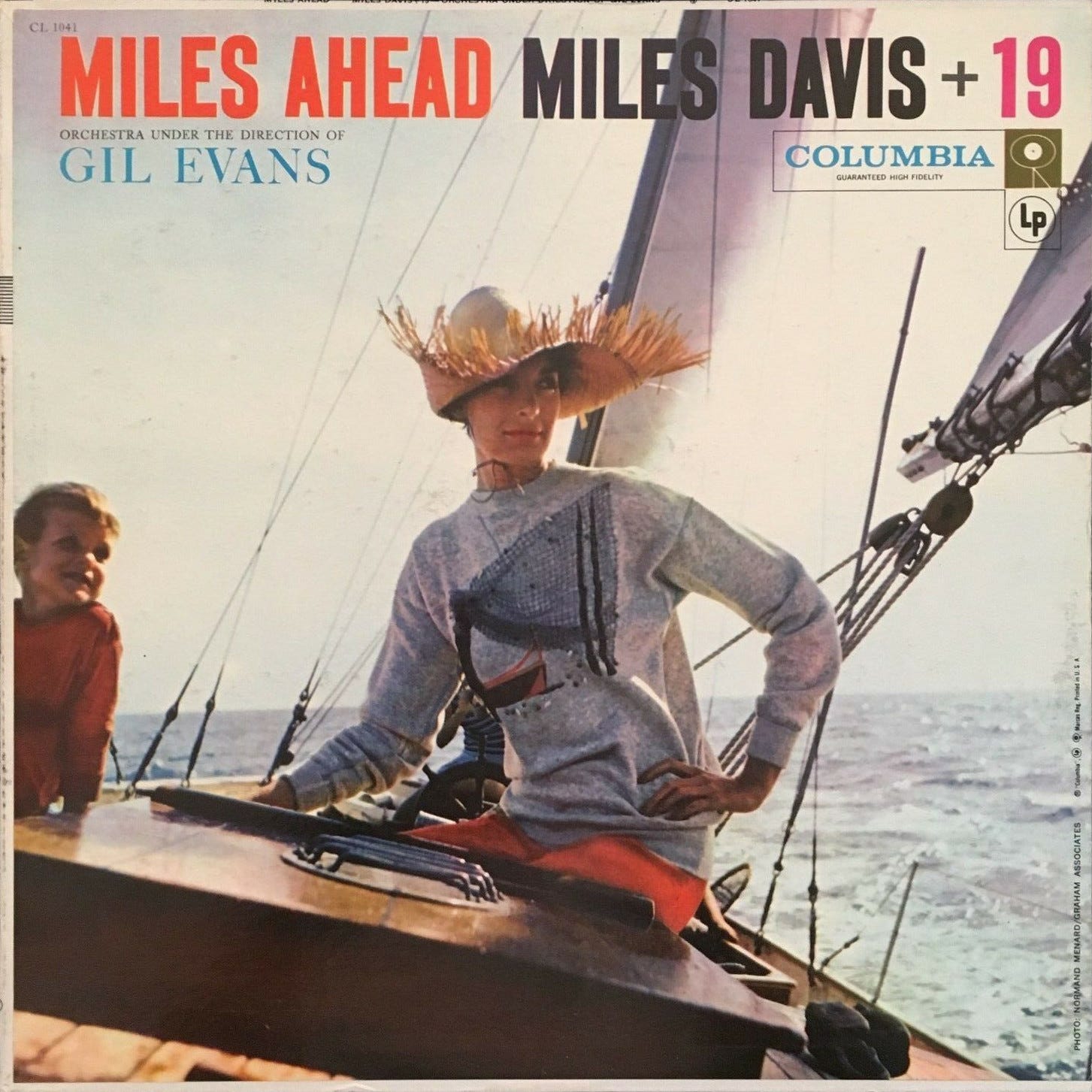

First of the three Columbia collaborations - noble attempts at bridging the jazz-classical divide - with Gil Evans, who coaxed even more heartbroken-modernism from Miles than was in to begin. I listen a lot to “The Duke”, Kurt Weill’s “My Ship” (though I miss Ira’s lyrics), “New Rhumba”, and especially the solo in “Miles Ahead”, the aching climax (0:58-1:20) that the album keeps teasing and which is simply one of the most beautiful things to spring from a human’s mouth (and hands). But I rarely listen to anything else — it’s too damn brassy for me! Harmonically, it’s Ellingtonian...but the swanky sheen feels closer to Nelson Riddle and those scotch-swilling Rat Pack douchebags. So, Gary Giddins: ‘Not since Ellington had any arranger extended the cross-harmonization between orchestral sections as rigorously as Evans[...]not since Ellington had any composer adapted the concerto to jazz as ingeniously[.] Evans realized that the cornerstone of Davis’s eloquence is his strength. Imbalance is not an issue. The ensemble motivates the soloist and is parried by him — the melancholy veracity of Davis’s timbre matches the plush brassy brilliance of Evans’s voicings.’ End after “New Rhumba” and you won’t miss much.

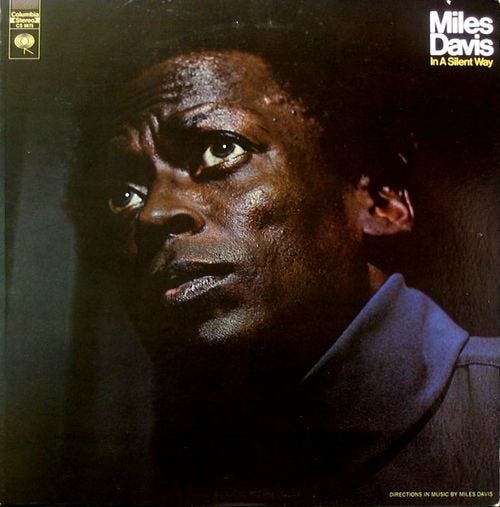

Fact is, it’s Joe Zawinul’s album as much as it is Miles’. Zawinul’s keyboards are what speckle us into this grazing twilight, this frightening new world; it’s his nebulous colors decorating the bowed bass + electric guitar combo in the first/last four minutes of side two (“In a Silent Way” — an opiate “Minstrel Boy”?) that everyone remembers best. Miles isn’t resting, though, because it’s his soloing - pained, scoping, dotting his messes - that raises the overall effect above ‘wallpaper.’ And it does threaten wallpaper, at times: side one, “Shhh/Peaceful”, runs out of ideas two-thirds through and just starts over; side two’s “It’s About That Time” section is diffuse, with a cadencing bit at the middle and end that’s…okay, but a very conventional and even dopey rock/soul groove compared to what, say, Sly Stone was doing, or even to Miles’ own “Stuff” a year prior. (This may speak to jazz’s failure to effectively absorb or interpolate the aspects of pop that it even actually did want to.) So: fusion! It’s like burning out and percolating at the same time: immersed in one’s own melancholy, but still trying to rise...not above, but beyond. A qualified cosmos.

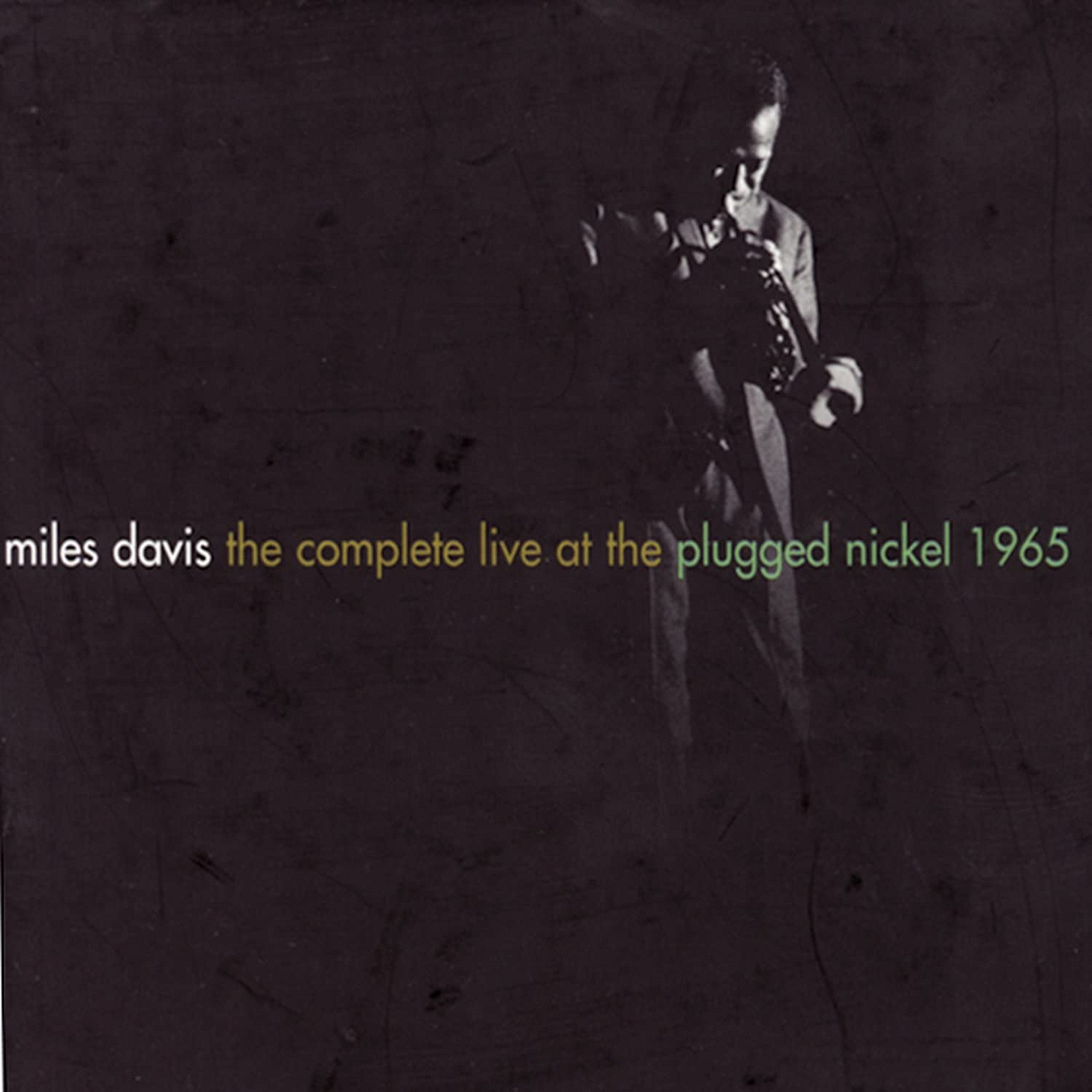

The only box set on this list, which I’m putting in exactly the #11 slot without thinking too much about it. Because you need this one. (Find a stream or download, unless you have $200 burning a hole in your pocket.) Eight discs, seven sets, recorded over two days in Chicago just before Christmas 1965, and everything good that’s been said about it is true: not only is it a privilege to hear one of the greatest bands in the world just getting used to each other, shifting gears in the face of the avant-garde without ever spazzing-out, but it’s also the only extended experience available to hear the second great quintet playing standards. Miles himself is having embouchure problems, and Herbie Hancock is tragically under-miked, but Wayne Shorter pushes himself deeper and deeper into the kooky nether-regions. Highlights include the first “‘Round Midnight” (disc two), the second “Stella by Starlight” (disc four) - which more fully adapts to the Kind of Blue touches that Hancock tries to give the first one - and Shorter’s flutterings in the final “Yesterdays”.