To Beguile the Time, Look Like the Time

On Joel Coen’s THE TRAGEDY OF MACBETH, and previous adaptations of the Scottish play

‘She wills it, he wills nothing, and paradoxically she collapses while he grows ever more frightening, outraging others, himself outraged, as he becomes the nothing he projects.’ — Harold Bloom, Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human (1998)

Given that Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth is a melding of my favorite writer and my favorite (living) filmmaker, I was predisposed to like it. Putting aside these predispositions as best I can, though, it does not seem necessarily regressive or reactionary to predict that the Shakespeare adaptation by the aging man with the ravishing images is…well, let’s just say it’ll probably be more interesting in the long arc of history than Licorice Pizza or Titane.

(2021 actually seemed like a marginally better year for film than the last few. I myself saw more new movies than ever last year - several dozen, including most of the ones that are filling out the big Top 10 lists - due in large part to a wonderful summer/fall job I had with the major film festival here in Halifax.)

In any case, there’s been a light sense of fatigue in many of the Tragedy of Macbeth reviews, though of course it still scores way-high on the tabulators. The objections vary: that Coen’s film is not suitably of the political moment; that the imagery upstages the poetry; that the language is too normalized.

That last one is at least a legitimate grievance. Much as it truly pains me to agree with even a single thing that The New Yorker’s Richard Brody says, some of Shakespeare’s poetry does get lost in the shuffle. As Macbeth, the great Denzel Washington - finally working with a director worthy of his awesome talent, after those misbegotten Tony Scott years - is occasionally too inward and casual with some of the play’s more nocturnal phantasmagoria. I would’ve liked a slower, creepier take on ‘Light thickens, and the crow makes wing to the rooky wood: good things of day begin to droop and drowse, while night’s black agents to their preys do rouse,’ which Denzel makes impulsive and conversational. Denzel’s Macbeth is, like so many of the Coens’ own creations, a deluded figure, somewhat less outwardly troubled than previous Macbeths by the knowledge that he will continue to do evil, but rather one who - like many Coen creations - believes that if they continue speaking, they can continue evading the inevitable. (Denzel’s clap during ‘Light thickens….’)

I must also confess to some weariness with Frances McDormand’s Lady Macbeth. Frankly, I’d like to see Coen stop defaulting to his wife as his ‘mature’ actress of choice. I know McDormand says that Lady Macbeth is the part she’s been auditioning her whole life for, but her ‘Come, thick night, and pall thee in the dunnest smoke of hell’ carried no dark erotic undercurrents for me at all, and her sleepwalking scene - though capped creepily enough with a ‘To bed!’ leveled at us the viewers - borders on unintentional comedy with her moans; I would’ve preferred the scene more tranced-out, messier, scarier.

There are stylistic miscalculations, too. The sound design is overcooked - lots of heavy swooshes - and there’s an effect when Birnam Forest approaches Dunsinane Castle where Denzel opens a window and a bunch of fake leaves burst through, an effect that can only be described as ‘corny’ — a word rarely leveled at Coen. And while the metastasizing of the witches - all three embodied by Kathryn Hunter, morphing from battlefield scavenger birds - is very, very clever and creepy, the expansion of the character of Ross (Alex Hassell) - i.e. Coen’s most significant embellishment on the play - is generally far less clever: there’s an irritating archness to many of his bits, which seems to confirm that Joel, rather than Ethan, was the one responsible for the dumber moments of ‘villain crush’ on the Javier Bardem character in No Country for Old Men (2007). There’s more than one scene with Ross in which Coen purposely evades showing us an important act of violence — a coy technique that reminded me of a line from Jonathan Rosenbaum’s negative review of No Country, a fine and gripping film two-thirds of the way, and the Coens’ dumbest movie beyond The Ladykillers (2004): Coen is ‘flattering the audience by suggesting they’re sophisticated enough to imagine the gorgeous carnage all by themselves.’

Ross here actually serves a similar function to the Bardem character in No Country: as a magnetic, yet also somewhat goofy, harbinger of demise. Roman Polanski, in his 1971 film of Macbeth, made Ross the elusive ‘third murderer’ of Banquo; Coen goes several steps beyond, emphasizing the character’s slippery-ness (though thankfully without making him superhuman; he’s still able to be talked down to) and making direct Shakespeare’s implication that Ross is privy to the slaughter of Lady Macduff and her children. However, Coen also includes a scene toward the end with Ross and Lady Macbeth that, on two viewings, strikes me as an absurd outrage.

Corey Hawkins as Macduff frankly doesn’t have the chops to make us feel enough devastation when he’s informed of his family’s slaughter; it’s a rather muted, underwhelming reaction. I also have to assume that Coen cut the scene of Malcolm ‘testing’ Macduff (‘Your wives, your daughters, your matrons and your maids, could not fill up the cistern of my lust…’) simply because Harry Melling’s odd face would just look too damn silly when talking lust.

There’s also an unfortunate ‘weightlessness’ to some of the violent deaths in Coen’s Macbeth, a weightlessness that was already apparent in those dopey CGI bullet-wounds in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs (2018) — surely not coincidentally, the first of now two Coen movies to be shot digitally. (2000’s O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) - whose opening shot of prison chains strewn across the sand is not dissimilar to the opening shot here, of the wounded captain’s trail of blood - was significant for being the first major film to be digitally color-corrected, while 2016’s Hail, Caesar! served as a late capstone to the celluloid era.)

With those many not-insignificant issues out of the way, though, I want to make it clear that there’s a lot to be grateful for in this Tragedy. Beyond the aforementioned factor of giving Denzel a movie worthy of his talent (the first time since 2012’s Flight, by my count), or the mesmerizing scenes with Hunter as the witches (speaking in a Cockney accent, and at one point ingeniously disguising herself as the ‘old man’; I laughed out loud at her delivery of ‘‘tis said they ate each other’), the main draw here is the visuals. Shot on sound-stages and then embellished with the ‘set effects’ of Stefan Dechant, Coen literally expands the scope of the stage, rendering a sublime balance between the very mediums. (Note the spotlight sound that opens and closes the film.) A full century after The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), Coen evokes at last the ‘cosmological wasteland’ that Harold Bloom so memorably pegged the world of Macbeth (and King Lear) as. Bloom called Macbeth the first Expressionist drama, and Coen, Dechant, and cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel (who shot some of Jean-Pierre Jeunet's later films, as well as the Coens’ 2013 Inside Llewyn Davis and the aforementioned Buster Scruggs) clearly agree: the sharp, clean architecture of Dunsinane Castle; the spidery shadows at play in the tent when Macbeth is greeted by the King; the high narrow walkway where the final battle between Macbeth and Macduff is fought.

While I actually wouldn’t rank The Tragedy of Macbeth’s black-and-white cinematography at quite the same ravishing level as Roger Deakins’ work on Coen’s previous black-and-white effort, The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001) - a film which objectively speaking might not even crack a Coens top 10, but which nevertheless remains one of my very favorites of theirs on a personal level - that’s likely due to the nature of celluloid vs. digital. Certain close-ups on human faces reminded me of the work of Carl Dreyer (an acknowledged influence on Coen here) and also of Sven Nykvist’s intensely-realized visages in his Ingmar Bergman films. The Coens have long been hailed for having very keen eyes for unique (or outright weird) human faces - probably the keenest since Fellini - and Joel puts that talent to work on this ‘wounded nature.’ Never before have I been made to focus so clearly on the poverty and desperation of the two murderers, or the sheepish terror of Lady Macbeth’s attendant during the sleepwalking scene, or the almost wistful wit in the brief conversation between Lady Macduff and her son — and their attendant, the ‘messenger.’ (‘I am not to you known, though in your state of honour I am perfect.’)

By almost any count, there have been three major screen adaptations of Macbeth: by Orson Welles (1948), Akira Kurosawa (1957’s Throne of Blood), and Roman Polanski (1971). (The less said about that embarrassment with Michael Fassbender, the better.) If you’re still skeptical about how much you really need to see another adaptation of one of the most well-trod texts of Western literature, consider that there hasn’t been a good Macbeth movie in literally 50 years. (And no good Shakespeare movies in 25.)

Welles’s version, typical of his career (and even more true of his 1951 Othello), was highly compromised by studio constraints. Its fogswept sets are often stunning to behold - glacier-like juts of rock, gnarled tree branches spidering up to the sky - but as an adaptation of the play, it’s barely adequate, with Welles over-emphasizing (read: hamming-up) some of the more phantasmagorical dialogue. (‘This…supernatural soliciting…cannot be ill…cannot be good….’) (Tallulah Bankhead, who declined the role of Lady Macbeth, would’ve helped.) (Seriously, how does anyone manage to make the Porter scene unfunny?) Welles also increased the presence of the witches, a desperate move. Chimes at Midnight (1965), in which Welles combined bits of Henry IV (Shakespeare’s best ‘histories’), Henry V, and the frivolous, tossed-off Merry Wives of Windsor, is Welles’s truly powerful (and uncompromised) Shakespeare film, giving Welles in Sir John Falstaff the character he was born to play. (No, not the other one.)

Polanski’s version, written with the Shakespeare scholar(/great critic) Kenneth Tynan, is pungent and freaky - Banquo’s ghost especially! - with a rough and wasted look to it, but its cast is disappointingly colorless: everyone’s competent, but nobody leaves much of an individual impression. Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood is the worthiest cinematic Macbeth, taking elements of the play - not the language - and re-setting the action in feudal Japan, with Kurosawa bringing a modernist Buddhist sensibility that blends with elements of kabuki theater in the acting (Isuzu Yamada is still the best onscreen Lady Macbeth) to make the film into something quite eerie, and into more of its own object than Welles’ or Polanski’s.

Polanski’s ambiguous ending trumps Coen’s ambiguous ending, and Kurosawa’s approaching of Birnam Wood - an unholy quaking of man and nature coupled in revolt - trumps everyone’s. (Polanski, perhaps wisely, didn’t even try to compete on that front.) But there’s a lot to be said for how Coen quickens-up Shakespeare’s ‘parallel editing’ - a technique even more prominent in Antony and Cleopatra, a play that’s just as great as Macbeth and yet still somehow hasn’t been adapted into an important movie - in order to bring out the thriller and film noir elements. (Coen has spoken in interviews about how much of American hard-boiled fiction is presaged in Shakespeare.)

(The figure most associated with modern cinematic Shakespeare is, of course, Kenneth Branagh, who I have highly mixed feelings about. His Much Ado About Nothing (1993) is terrible; his Henry V (1989) is sometimes quite gripping but also seems ironically more dated to its time than Laurence Olivier’s (1944), and is a thoughtlessly hypocritical movie to boot. (Oh, poor tortured King Henry, so pained by the horrors of war. Never mind that he started the war back in act one, and has no intention of giving back any of the things he got by winning it.) (Thrilling score, though! Patrick Doyle is underrated.) And yet, Branagh’s Hamlet (1996), for all its many dumb decisions - and there are many - is still probably the best version I’m ever likely to see on screen or stage — at least it’s the whole thing, and it looks good.)

Given that Macbeth is basically the original ‘horror noir,’ it makes sense that it would be this play that drew Coen in, rather than any of the other ones. (Though just for fun, consider: Fargo (1996) is the Coens’ King Lear, a popular masterpiece that is, in fact, soul-crushingly bleak; Burn After Reading (2008) is their Measure for Measure, a hilarious cesspool in which the creators actually do, for once, have genuine disdain for most of their characters.) Coen, who started as an editor on Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead (1981), has presided over many scenes over the course of his career that could fit neatly into straight-up horror films: several sequences in Blood Simple (1984), especially the ending; the hotel climax of Barton Fink (1991); the initial murders on that deep-night highway in Fargo; the central cat-and-mouse suspense sequence in No Country for Old Men. Hell, even the “Meal Ticket” segment of The Ballad of Buster Scruggs gives me the willies, with its grim-glowing visual palette and its pervasive sinking feeling. Macbeth, a play set in a fallen world - practically a mythological land - with characters ‘falling in time,’ makes sense in this lineage, right down to Carter Burwell’s terrific gothic-horror music that plays under the title card. (‘Peace — the charm’s wound up.’)

The chatter about whether the Coen brothers have ‘split up,’ chatter which started as soon as Joel’s solo outing was announced, is pretty mindless. Folks, let’s put two and two together: Joel went to film school and started in a cutting room. Ethan took philosophy and writes poetry and plays. Putting it as bluntly as possible, Joel is the ‘film guy,’ while Ethan the ‘writing guy’ (and likely, more the humorist of the pair.) Of course there’s plenty of overlap, but the Coens’ longtime composer Carter Burwell used pretty much those exact words in a recent documentary interview. So it shouldn’t be any surprise that Ethan wasn’t interested in a Shakespeare adaptation where roughly 80% of the Bard’s dialogue is left intact.

If you’ll forgive the highbrow analogy - although, ain’t we talkin’ Shakespeare? - I’d liken the Coens’ position in their field as something like no less than Mozart’s. Not in terms of the effect of their art, of course; Mozart is a humanist and (ultimately) a mystic who sees meaning everywhere, while the Coens are existentialists who worry that they live in a nihilistic universe. (I’d say the essence of the Coen brothers is the combination of Kafka and Kubrick.) Rather, in terms of how both Mozart and the Coens produce works that are both ‘difficult’ - enough that a lot of connoisseurs in their own time complain about it a lot (including smart people like Jonathan Rosenbaum, Pauline Kael, and Dave Kehr, the last of whom set the high bar for hilariously tortured Coen-hate when he actually alleged, in a review of No Country for Old Men, that the Coens want us to laugh at the linoleum floor that a cop gets strangled to death on) - and, sometimes, popular. I sure hope Coen’s movie doesn’t win the Best Picture Oscar; the ensuing backlash would be far too dumb to take.

And yet The Tragedy of Macbeth is still getting a somewhat muted reaction in comparison with other more ‘timely’ movies. Violet Lucca wrote a review of the film in Reverse Shot from the New York Film Festival - a very good review, typical of Lucca and of the website in general - where she praised the film but said that it paled in comparison to other, more consciously contemporary titles from NYFF 2021 like Radu Jude’s Bad Luck Banging Club or Loony Porn, Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir Part II, and Kiro Russo’s El Gran Movimiento. I haven’t seen The Souvenir Part II or El Gran Movimiento yet - though I reckon it’s safe to say that the former, if it’s anything like its progenitor, is probably a film of limited visual interest, at least - but the citation of Bad Luck Banging Club bespeaks an eagerness with which even smart critics will fall for a movie that simply depicts the current moment, whether or not it actually has anything to say about it. (Jude’s is a film with a mesmerizing first ‘segment’ that’s soon undone by a pompous second one. It’s almost touching to see how so many politically-minded Eastern European filmmakers are still doing their damndest to ensure that nobody who might be convinced by their politics would ever actually see their movies in the first place.) Again, I haven’t seen two of the three films Lucca cited, but I still can’t help but be reminded of a line from pop music critic Robert Christgau, writing about the ‘90s/‘00s onslaught of ‘post-rock’ albums: that these are the kinds of works that ‘get nothing but raves because only believers bother to listen.’

Sorry folks, but I need big and powerful images. Show me something beautiful, please, for the love of God show me something beautiful. I like following auteur theory too, but not to such an extent that I care more about what Joel Coen’s movie says about Joel Coen than I do about whether or not his movie can hold me in its grip.

Curious side note: Joel Coen has had good luck with birds in his career. Remember that shadow of the flock passing over the sunny, empty highway toward the end of Blood Simple? Or the gull dive-bombing into the ocean in the last shot of Barton Fink? Or the very first thing we see in Fargo, a faint shot of a bird struggling against the all-encompassing snow and wind? Maybe the fake birds in The Tragedy of Macbeth are Coen’s roundabout way of returning the favor, lest his monuments be the maws of kites!

And hey, at the very least, let us all thank Baal that there’s finally a movie in theaters that’s under two hours. Seriously, nearly every major movie that’s been playing for the last few weeks (months?) has been upwards of 130 minutes, from The Matrix Resurrections to West Side Story to House of Gucci to Licorice Pizza to fucking Spider-Man. Gimme something brisk! And that I can fucking look at without falling asleep!!!!

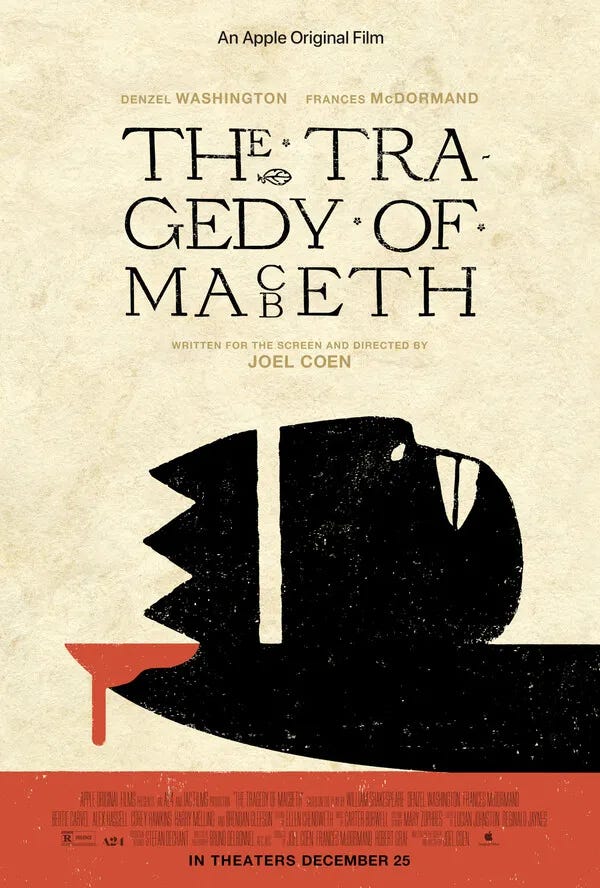

Also, something I think we can all agree on: best movie poster of 2021.

— — —

A Substack update

When I started this Substack a few months ago, I said that posts would be coming ‘fortnightly’ posts. Given how long these posts usually are, this was incredibly optimistic - ‘monthly’ has been more accurate - especially considering that I also intended to be working on a book at the same time. I’m starting to buckle down on said book, which requires a lot of research. Thus, you can expect even less regularity with these posts from now on!